The United States total public debt, commonly called the national debt, or U.S. government debt, is the amount of money owed by the United States federal government to creditors who hold U.S. debt instruments. Debt held by the public is all federal debt held by states, corporations, individuals, and foreign governments, but does not include intragovernmental debt obligations or debt held for Social Security. Types of securities held by the public include, but are not limited to, Treasury Bills, Notes, Bonds, TIPS, United States Savings Bonds, and State and Local Government Series securities.[1]

As of March 2008, the total U.S. federal debt was approximately $9.4 trillion[2], about $79,000 in average for each American taxpayer. Of this amount, debt held by the public was roughly $5.3 trillion.[3] If, in addition, unfunded Medicaid, Social Security, etc. promises are added, this figure rises to a total of $59.1 trillion.[4] In 2007 the public debt was 36.8 percent of GDP ranking 65th in the world.[5]

It is important to differentiate between public debt and external debt. The former is the amount owed by the government to its creditors, whether they are nationals or foreigners. The latter is the debt of all sectors of the economy (public and private), owed to foreigners. In the U.S., foreign ownership of the public debt is a significant part of the nation's external debt (see also below). The Bureau of the Public Debt, a division of the United States Department of the Treasury, calculates the amount of money owed by the national government on a daily basis.

Calculating and projecting the debt

Tracking current levels of debt is a cumbersome but rather straightforward process. Making future projections is much more difficult for a number of reasons. For example, before the September 11, 2001 attacks, the George W. Bush administration projected in the 2002 U.S. Budget that there would be a $1.288 trillion surplus from 2001 through 2004.[6] In the 2005 Mid-Session Review, however, this had changed to a projected deficit of $850 billion, a swing of $2.138 trillion.[7] The latter document states that 49 percent of this swing was due to "economic and technical re-estimates," 29 percent was due to "tax relief," (mainly the 2001 and 2003 Bush tax cuts, and the remaining 22 percent was due to "war, homeland, and other enacted legislation" (mainly expenditures for the War on Terror, Iraq War, and homeland security).

Projections between different groups will sometimes differ because they make different assumptions. For example, in August 2003 a Congressional Budget Office report projected a $1.4 trillion deficit from 2004 through 2013.[8]

However, a mid-term and long-term joint analysis a month later by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, the Committee for Economic Development, and the Concord Coalition stated that "In projecting deficits, CBO follows mechanical 'baseline' rules that do not allow it to account for the costs of any prospective tax or entitlement legislation, no matter how likely the enactment of such legislation may be." The analysis added in a proposed tax cut extension and Alternative Minimum Tax reform (enacted by a 2005 act), prescription drug plan (Medicare Part D, enacted in a 2003 act), and further increases in defense, homeland security, international, and domestic spending. According to the report, this "adjusts CBO's official ten-year projections for more realistic assumptions about the costs of budget policies," raising the projected deficit from $1.4 trillion to $5 trillion.[9]

The mechanics of U.S. Government debt

When the expenses of the U.S. Government exceed the revenue collected, it issues new debt to cover the deficit. This debt typically takes the form of new issues of government bonds which are sold on the open market. However, the debt can also be monetized by which the Federal Reserve creates an entry on its books to credit the US Government for an amount equal to the dollar amount of the bonds the Federal Reserve is acquiring. The money created in this process not only includes the new dollars that came into existence just to purchase the bonds, but much more because this new money is now sitting in the form of checkbook money at the Federal Reserve. Under the scheme of Fractional Reserve Banking this new checkbook money is treated as an asset to lend against. Economists estimate the expansion of the money supply as being many times the amount of the initial money created with the exact amount being a function of what percentage of deposits banks must set aside as "reserves".[10][11]

The ultimate consequence of monetizing U.S. debt is that it expands the money supply which will tend to dilute the value of dollars already in circulation. Thus, expanding the pool of money puts downward pressure on the dollar, downward pressure on short-term interest rates (the banks have more to lend) and upward pressure on inflation. Typically this causes an inflationary boom that ends in a deflationary bust to complete the business cycle. Note that money supply expansion is not the only force at work in inflation or interest rates. United States Dollars are essentially a commodity on the world market and the value of the dollar at any given time is subject to the law of supply and demand. In recent years, the debt has soared and inflation has stayed low in part because China has been willing to accumulate reserves denominated in U.S. Dollars. Currently, China holds over $1 trillion in dollar denominated assets (of which $330 billion are U.S. Treasury notes). In comparison, $1.4 trillion represents M1 or the "tight money supply" of U.S. Dollars which suggests that the value of the U.S. Dollar could change dramatically should China ever choose to divest itself of a large portion of those reserves.[12][13][14][15]

The US budget deficit has been declining for the last three years and the Congressional Budget Office projects a surplus by 2012. [16] When the U.S. Government has a surplus, it may pay down its outstanding debt. It does this by paying back the principal of the outstanding bonds redeemed for payment while not issuing new bonds. The U.S. Government could also purchase its own outstanding securities on the open market if it was searching for a way to use a surplus to reduce outstanding debt that was not due for redemption in a given year. [10] [11]

U.S. Government debt and trade deficits

Classical macroeconomic theory defines national savings as the summation of the savings of all individuals and businesses in a nation plus the savings of that nation's government. According to classical theory:

- Net exports = national savings - investments

which would mean that were national savings to decline due to government deficits, either investments must also decline or the country must import capital (i.e. run a trade deficit). Since the 1960s, the trade balance of the United States has run its highest trade deficits during those decades where it was running the highest national deficits as theory would predict.[17] In recent years, the US trade deficit has reached roughly 6% of the GDP, a level former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker calls unsustainable.[18]

Arguments against paying down the national debt

Since the money supply is reduced when the U.S. Government pays down its debt, the unintended result of a government surplus could be a deflationary recession as the money supply contracts in the reverse of the process of monetization described above. The government can avoid this consequence by instead focusing on expanding its GDP and thereby "reducing" the percentage of GDP that debt represents. The hope is that the deficit spending that increases the debt will increase GDP by a greater amount, and thus in relative terms, at least the debt would decrease. This worked to great effect in the U.S. between the end of World War II and 1980, even though the debt showed a net increase in absolute value over the same period.[19] Kenneth L. Fisher's May 1, 2007, article "Learning to Love Debt" is a good representation of the argument that "more debt is [a] good thing" because of after effects the resulting money creation will have on the economy.[20]

Arguments for paying down the national debt

Economists from the Austrian School point out that the United States experienced depreciation of 43% of CPI (from CPI of 51 to 29) from 1800-1912: a period of strong economic growth in U.S. history.[21] [22][23]

Furthermore, those who would argue that an expansion of the money supply is necessary to expand the economy need to explain the colossal failure of Japan's Central Bank to do just that. In an attempt to follow Keynesian economics and spend itself out of a recession, Japan's central bank engaged in no fewer than 10 stimulus programs over the 1990s that totalled over 100 trillion yen.[24] This did nothing to cure Japan's recession and has instead left the nation with a national debt that is 158% of GDP.[25]

In the absence of debt monetization, when the Government borrows money from the savings of others, it consumes the amount of savings there are to lend. If the government were to borrow less, that money would be freed to work in the private sector and would lower interest rates overall.

Lastly, raising interest rates is one of the traditional ways that the U.S. Federal Reserve uses to combat inflation (which can be brought on by government debt), but a large national debt figure makes it difficult to do so because it raises the interest paid in servicing that debt. [10]

Risks and obstacles

Risks to the U.S. dollar

By definition, international trade is the exchange of goods and services across national borders. Historically the currencies of nations involved were backed by precious metals (typically using some form of Gold Standard), which would cause a nation operating under a trade imbalance to send precious metals (economic goods in and of themselves) to correct any trade imbalances. In the current scheme of fiat money, the U.S. government is free to print all the money it wants. Consequentially, the government cannot technically go bankrupt as any debtor nation can just issue more money through a practice known as seigniorage.[26]

If there is a gross imbalance between the amount of new money being brought into circulation and the amount of economic goods that are represented by an economy, then there is an unstable situation that can lead to hyperinflation.[27] This has been observed in smaller nations such as Argentina in 1989; the International Monetary Fund and World Bank try to end such crises by working with the problem country to institute sound economic policies and restore faith in the international community that the country can again service its debt with a stable currency.[28]

The interest rate offered on new bond issues is the one that clears the market. On December 13 2006, the U.S. 30 year treasury note had a rate of 5.375%. Were investors to become concerned about the future value of the US Dollar, they would demand a higher interest rate on US bonds to compensate them for the risk they are assuming.[29]

In 2006, Professor Laurence Kotlikoff argued the United States must eventually choose between "bankruptcy," raising taxes, or cutting payouts. He assumes there will be ever-growing payment obligations from Medicare and Medicaid.[30] Others who have attempted to bring this issue to the fore of America's attention range from Ross Perot in his 1992 Presidential bid, to Investment guru Robert Kiyosaki, David Walker, head of the Government Accountability Office, and most recently, 2008 Presidential Candidate Ron Paul.[31][32]

Amount of foreign ownership of U.S. debt

A traditional defense of the national debt is that we "owe the debt to ourselves", but that is increasingly not true. The US debt in the hands of foreign governments is 25% of the total[33], virtually double the 1988 figure of 13%.[34] Despite the declining willingness of foreign investors to continue investing in dollar denominated instruments as the US Dollar has fallen in 2007,[35] the U.S. Treasury statistics indicate that, at the end of 2006, foreigners held 44% of federal debt held by the public.[36] About 66% of that 44% was held by the central banks of other countries, in particular the central banks of Japan and China. In total, lenders from Japan and China held 47% of the foreign-owned debt.[37] Some argue this exposes the United States to potential financial or political risk that either banks will stop buying Treasury securities or start selling them heavily. In fact, the debt held by Japan reached a maximum in August of 2004 and has fallen nearly 3% since then.[38]

In 2006, the central banks of Italy, Russia, Sweden, and the United Arab Emirates announced they would reduce their dollar holdings slightly, with Sweden moving from a 90% dollar based foreign reserve to 85%. [39] On May 20, 2007, Kuwait discontinued pegging its currency exclusively to the dollar preferring to use the dollar in a basket of currencies.[40] Syria made a similar announcement on June 4th, 2007.[41]

A brief history of the debt

- See also: National debt by U.S. presidential terms

The United States has had public debt since its inception. Debts incurred during the American Revolutionary War and under the Articles of Confederation led to the first yearly reported value of $75,463,476.52 on January 1, 1791. Over the following 45 years, the debt grew, briefly contracted to zero on January 8, 1835 under President Andrew Jackson but then quickly grew into the millions again.[42][43]

The first dramatic growth spurt of the debt occurred because of the Civil War. The debt was just $65 million in 1860, but passed $1 billion in 1863 and had reached $2.7 billion following the war. The debt slowly fluctuated for the rest of the century, finally growing steadily in the 1910s and early 1920s to roughly $22 billion as the country paid for involvement in World War I.[44]

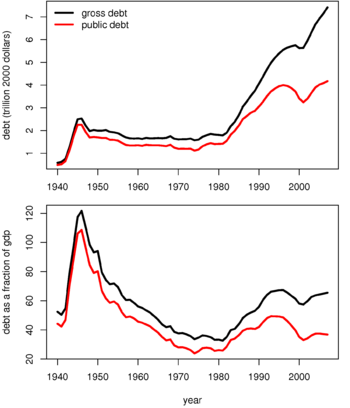

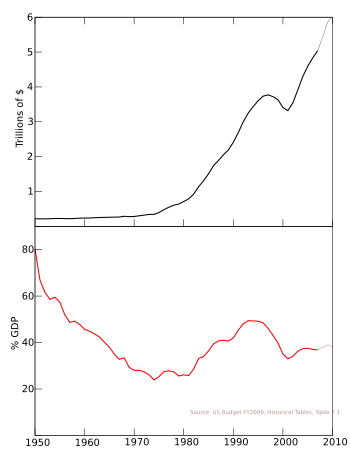

The buildup and involvement in World War II brought the debt up another order of magnitude from $51 billion in 1940 to $260 billion following the war. After this period, the debt's growth closely matched the rate of inflation until the 1980s, when it again began to increase rapidly. Between 1980 and 1990, the debt more than tripled. The debt shrank briefly after the end of the Cold War, but by the end of 2005, the gross debt had reached $7.9 trillion, about 8.7 times its 1980 level.[45]

| End of Fiscal Year |

US Public Debt USD billions[46] |

% of GDP[47] |

|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 2.6 | |

| 1920 | 25.9 | |

| 1930 | 16.2 | |

| 1940 | 43.0 | 44.2 |

| 1950 | 257.4 | 80.2 |

| 1960 | 290.2 | 45.7 |

| 1970 | 389.2 | 28.0 |

| 1980 | 930.2 | 26.1 |

| 1990 | 3233 | 42.0 |

| 2000 | 5674 | 35.1 |

| 2005 | 7933 | 37.4 |

| 2007 | 9008 | 36.8 |

| 2008 | 37.9(est) |

At any given time (at least in recent decades), there is a debt ceiling in effect. Whereas Congress once approved legislation for every debt issuance, the growth of government fiscal operations in the 20th century made this impractical. (For example, the Treasury now conducts more than 200 sales of debt by auction every year to fund $4 trillion in debt operations.) The Treasury was granted authority by the Congress to issue such debt as was needed to fund government operations as long as the total debt (excepting some small special classes) did not exceed a stated ceiling. However, the ceiling is routinely raised by passage of new laws by the United States Congress every year or so. The most recent example of this occurred in September 2007, when the Congress raised the debt limit to $9.815 trillion.[48]

Debt clocks

In several cities around the United States, there are national debt clocks electronic billboards which supposedly show the amount of money owed by the government. Some also attempt to show the money owed per capita or per family. There is a significant level of fluctuation day-to-day, both up and down, so any "clocks" must be continually re-set with proper values.

The most famous debt clock, located in Times Square[49] in New York City, was created by eccentric real estate mogul Seymour Durst. The clock is now owned by his son Douglas Durst. Durst's clock was deactivated in 2000 when the debt began to decrease. However, following large increases, the clock was reactivated a few years later, though had to be moved to make way for One Bryant Park. According to Durst the National debt is now increasing at such a rate that his clock will be obsolete (for lack of digits) when the debt reaches the $10 trillion mark, expected in Spring 2009.[50]

There is an online debt clock at: brillig A free debt clock for web sites is available at: zFacts

Recent additions to the public debt of the United States

| Fiscal year (begins 10/01) |

Value | % of GDP |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | $144.6 billion | 1.4% |

| 2002 | $409.3 billion | 3.9% |

| 2003 | $589.0 billion | 5.5% |

| 2004 | $605.0 billion | 5.3% |

| 2005 | $523.2 billion | 4.3% |

| 2006 | $536.5 billion | 4.1% |

| 2007 | $527.9 billion | 3.9% |

The

cumulative debt of the United States in the past

5 completed fiscal years was approximately $2,782

billion, or about 29.5% of the total national debt

of ~$9.4 trillion.[51][52]

Statistics and comparables

- U.S. official gold reserves are worth $261.5 billion(as of March 2008), foreign exchange reserves $63 billion[citation needed] and the Strategic Petroleum Reserve $77 billion (at a Market Price of $110/barrel).

- The national debt equates to $30,400 per person U.S. population, or $60,100 per head of the U.S. working population,[53] as of February 2008.

- In 2003 $318 billion was spent on interest payments servicing the debt, out of a total tax revenue of $1,952 billion.[54]

- Total U.S. household debt, including mortgage loan and consumer debt, was $11,400 billion in 2005. By comparison, total U.S. household assets, including real estate, equipment, and financial instruments such as mutual funds, was $62,500 billion in 2005.[55]

- Total U.S Consumer Credit Card revolving credit debt was $937.5 billion in November 2007.[56]

- Total third world debt was estimated to be $1,300 billion (or $1.3 trillion) in 1990.[57]

- The U.S. balance of trade deficit in goods and services was $725.8 billion in 2005.[58]

- The global market capitalization for all stock markets was $43,600 billion (or $43.6 trillion) in March 2006.

References

- US GAO Financial Audit: Bureau of the Public Debt's Fiscal Years 2004 and 2003 Schedules of Federal Debt GAO-05-116 November 5, 2004.

- U.S. National Debt Clock

- http://www.treasurydirect.gov/govt/reports/pd/feddebt/feddebt_daily.htm

- http://www.usatoday.com/news/washington/2007-05-28-federal-budget_N.htm?csp=34

- https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2186rank.html

- "Fiscal Year 2000: Budget of the United States Government." Office of Management and Budget, Executive Office of the President. Government Printing Office 2003. 2002 U.S. Budget.

- "Fiscal Year 2005 Mid-Session Review: Budget of the United States Government." Office of Management and Budget, Executive Office of the President. 2005. [1]

- "The Budget and Economic Outlook: An Update." Congressional Budget Office, Congress of the United States. August 2003 [2]

- "Mid-term and long-term deficit projections." Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Committee for Economic Development, and Concord Coalition. 29 Sept. 2003.[3]

- "The Macro Economy Today" by Bradley Schiller;

- "Secrets of the Temple" by William Greider.

- http://www.ustreas.gov/tic/mfh.txt

- http://www.economist.com/finance/displaystory.cfm?story_id=8083036

- http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h6/current/

- http://www.telegraph.co.uk/money/main.jhtml?xml=/money/2007/08/07/bcnchina107a.xml

- http://www.cbo.gov/

- Macroeconomics, 6th Ed. by Gregory Mankiw P. 128-129

- http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A38725-2005Apr8.html

- http://www.gpoaccess.gov/usbudget/fy07/pdf/hist.pdf

- http://www.financial-planning.com/pubs/fp/20070501014.html

- http://www.lib.umich.edu/govdocs/historiccpi.html

- http://www.optimist123.com/optimist/2006/07/paying_down_the.html

- www.rodgermitchell.com

- http://www.mises.org/story/1099

- https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ja.html#Econ

- "A History of Money and Banking in the United States" by Dr. Murray Rothbard

- Macroeconomics 6th Edition by Gregory Mankiw P. 106-108

- http://www.internationalmonetaryfund.com/External/NP/ieo/2003/arg/index.htm

- http://www.iht.com/articles/2007/09/13/news/econ.php

- http://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/review/06/07/Kotlikoff.pdf

- http://finance.yahoo.com/columnist/article/richricher/10932

- http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2006/10/28/business/main2135398.shtml

- http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/17424874/

- Amadeo, Kimberly. The U.S. Debt and How It Got So Big. About.com.

- http://www.parapundit.com/archives/004619.html

- http://www.gpoaccess.gov/usbudget/fy08/pdf/spec.pdf

- http://www.treas.gov/tic/mfh.txt

- http://www.treas.gov/tic/mfh.txt

- http://asia.news.yahoo.com/060803/3/2nzd0.html

- http://www.forbes.com/markets/feeds/afx/2007/05/20/afx3739653.html

- Bloomberg.com: Worldwide. Retrieved on 2007-11-04.

- http://www.publicdebt.treas.gov/opd/opdhisto1.htm

- http://www.publicdebt.treas.gov/opd/opdhisto2.htm

- http://www.treasurydirect.gov/govt/reports/pd/histdebt/histdebt.htm

- http://www.gpoaccess.gov/usbudget/fy07/pdf/hist.pdf

- http://www.treasurydirect.gov/govt/reports/pd/histdebt/histdebt.htm

- http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/fy2009/pdf/hist.pdf

- UPDATE 1-U.S. Senate agrees to raise U.S. credit limit.

- http://www.theledger.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20060514/NEWS/605140354/1036

- Historical tables, FY 2009 U. S. Budget

- U.S. Treasury website

- Bureau of Economic Analysis

- http://www.bls.gov/cps/cps_over.htm#overview

- IRS Collections by State and Type 1998-2006.

- http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/

- FRB: G.19 Release-Consumer Credit. Retrieved on 2008-02-04.

- http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/ThirdWorldDebt.html#further

- http://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/statistics/highlights/annual.html

- Wright, Robert (2008). One Nation Under Debt: Hamilton, Jefferson, and the History of What We Owe. Mc-Graw Hill. . Argues that America completely paid off its first national debt but is unlikely to do so again.

- Bonner, William; Wiggin, Addison (2006). Empire of Debt: the Rise of an Epic Financial Crisis. Wiley. Argues that America is a world empire that uses credit in lieu of tribute and that history shows this to be unsustainable.

- Cavanaugh, Frances X. (1996). The Truth About the National Debt: Five Myths and One Reality. Argues that the US is in good economic condition and that talk of the consequences of its debt is unduly alarmist.

- Hargreaves, Eric L. (1966). The National Debt.

- Macdonald, James (2006). A Free Nation Deep in Debt: The Financial Roots of Democracy. Princeton University Press. Argues that democracies eventually defeat autocracies because "countries with representative institutions are able to borrow more cheaply than those with autocratic governments" (p. 4). Bond markets also strengthen democracies internally by giving citizens some of the proverbial power of the purse and by aligning their interests with those of their governments.

- Rothbard, Murray Newton (1994). The Case Against the Fed. Describes the process of debt monetization by a nation's central bank and it's unfortunate consequences on society.

- Taylor, George Rogers (ed.) (1950). Hamilton and the National Debt.

External links

- Bureau of the Public Debt

- U.S. Debt News via HavenWorks.com News

- Read Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding the U.S. Federal Debt

- The United States Public Debt, 1861 to 1975

- Public Debt Issues, 1775-1976

- The Budget Graph: A graphical representation of the 2007 United States federal discretionary budget, including the public debt.

- Federal Budget

- Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding the U.S. budget deficit

- The U.S. 'could be going bankrupt' according to U.S. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis official

- Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding the U.S. budget deficit

- External debt as a % of GDP / Total Debt External debt ( data from 1995) as 1) % of GDP and 2) as a % of total debt

- Federal Receipts as Percent of National Debt Table and graph of federal income calculated as a percent of national debt (1901-2006)

- The Total Debt, analysis by a private citizen.