|

|

Treasury

securities

are government bonds issued by the United States Department

of the Treasury through the Bureau of the Public Debt. They

are the debt financing instruments of the U.S. Federal government,

and they are often referred to simply as Treasuries

or Treasurys. There are four types of marketable

treasury securities: Treasury bills, Treasury notes, Treasury

bonds, and Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS)

There

are several types of non-marketable treasury securities

including State and Local Government Series (SLGS), Government

Account Series debt issued to government-managed trust funds,

and Savings bonds. All of the marketable Treasury securities

are very liquid and are heavily traded on the secondary

market. The non-marketable securities (such as savings bonds)

are issued to subscribers and cannot be transferred through

market sales.

|

|

Marketable Securities

Directly

issued by the US Government -- Treasury

bill

Treasury

bills (or T-bills) mature in one year or less. Like

zero-coupon bonds, they do not pay interest prior to maturity;

instead they are sold at a discount of the par value to create

a positive yield to maturity. Many regard Treasury bills as the

least risky investment available to U.S. investors.

Regular weekly

T-Bills are commonly issued with maturity dates of 91 days (or

13 weeks, about 3 months), and 182 days (or 26 weeks, about 6

months). Treasury Bills are sold by single price auctions held

weekly. Offering amounts for 13-week and 26-week bills are announced

each Thursday for auction at 1:00 pm on the following Monday and

settlement, or issuance, on Thursday. Offering amounts for 4-week

bills are announced on Monday for auction the next day, Tuesday,

at 1:00 pm and issuance on Thursday. Purchase orders at TreasuryDirect

must be entered before 11:30 on the Monday of the auction. The

minimum purchase amount is $1,000. (This amount formerly had been

$10,000.) Mature T-bills are also redeemed on each Thursday. Banks

and financial institutions, especially primary dealers, are the

largest purchasers of T-Bills.

Like other

securities, individual issues of T-bills are identified with a

unique CUSIP number. The 13-week bill issued three months after

a 26-week bill is considered a re-opening of the 26-week bill

and is given the same CUSIP number. The 4-week bill issued two

months after that and maturing on the same day is also considered

a re-opening of the 26-week bill and shares the same CUSIP number.

For example, the 26-week bill issued on March 22, 2007 and maturing

on September 20, 2007 has the same CUSIP number (912795A27) as

the 13-week bill issued on June 21, 2007 and maturing on September

20, 2007, and as the 4-week bill issued on August 23, 2007 that

matures on September 20, 2007.

During periods

when Treasury cash balances are particularly low, the Treasury

may sell cash management bills (or CMBs). These are sold

at a discount and by auction just like weekly Treasury bills.

They differ in that they are irregular in amount, term (often

less than 21 days), and day of the week for auction, issuance,

and maturity. When CMBs mature on the same day as a regular weekly

bill, usually Thursday, they are said to be on-cycle. The

CMB is considered another reopening of the bill and has the same

CUSIP. When CMBs mature on any other day, they are off-cycle

and have a different CUSIP number.

Treasury bills

are quoted for purchase and sale in the secondary market on an

annualized percentage yield to maturity, or basis.

With the advent

of TreasuryDirect, individuals can now purchase T-Bills online

and have funds withdrawn and deposited directly to their personal

bank account and earn higher interest rates on their savings.

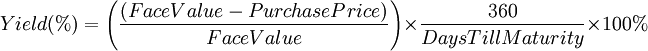

General calculation

for yield on Treasury bills is

Treasury

note

Treasury

notes (or T-Notes) mature in two to ten years. They

have a coupon payment every six months, and are commonly issued

with maturities dates of 2, 5 or 10 years, for denominations from

$1,000 to $1,000,000.

T-Notes and

T-Bonds are quoted on the secondary market at percentage of par

in thirty-seconds of a point. Thus, for example, a quote of 95:07

on a note indicates that it is trading at a discount: $952.19

(i.e. 95 7/32%) for a $1,000 bond. (Several different notations

may be used for bond price quotes. The example of 95 and 7/32

points may be written as 95:07, or 95-07, or 95'07, or decimalized

as 95.21875.) Other notation includes a +, which indicates 1/64

points and a third digit may be specified to represent 1/256 points.

Examples include 95:07+ which equates to (95 + 7/32 + 1/64) and

95:073 which equates to (95 + 7/32 + 3/256). Notation such as

95:073+ is unusual and not typically used.

The 10-year

Treasury note has become the security most frequently quoted when

discussing the performance of the U.S. government-bond market

and is used to convey the market's take on longer-term macroeconomic

expectations.

Treasury

bond

Treasury

bonds (T-Bonds, or the long bond) have the longest

maturity, from ten years to thirty years. They have coupon payment

every six months like T-Notes, and are commonly issued with maturity

of thirty years. The secondary market is highly liquid, so the

yield on the most recent T-Bond offering was commonly used as

a proxy for long-term interest rates in general. This role has

largely been taken over by the 10-year note, as the size and frequency

of long-term bond issues declined significantly in the 1990s and

early 2000s.

The U.S. Federal

government stopped issuing the well-known 30-year Treasury bonds

(often called long-bonds) on October 31, 2001. As the U.S. government

used its budget surpluses to pay down the Federal debt in the

late 1990s, the 10-year Treasury note began to replace the 30-year

Treasury bond as the general, most-followed metric of the U.S.

bond market. However, due to demand from pension funds and large,

long-term institutional investors, along with a need to diversify

the Treasury's liabilities - and also because the flatter yield

curve meant that the opportunity cost of selling long-dated debt

had dropped - the 30-year Treasury bond was re-introduced in February

2006 and is now issued quarterly. This will bring the U.S. in

line with Japan and European governments issuing longer-dated

maturities amid growing global demand from pension funds. Some

countries, including France and the United Kingdom, have begun

offering a 50-year bond, known as a Methuselah.

TIPS

Treasury

Inflation-Protected Securities (or TIPS) are the inflation-indexed

bonds issued by the U.S. Treasury. These securities were first

issued in 1997. The principal is adjusted to the Consumer Price

Index, the commonly used measure of inflation. The coupon rate

is constant, but generates a different amount of interest when

multiplied by the inflation-adjusted principal, thus protecting

the holder against inflation. TIPS are currently offered in 5-year,

7-year, 10-year and 20-year maturities. 30-year TIPS are no longer

offered.

In addition

to their value for a borrower who desires protection against inflation,

TIPS can also be a useful information source for policy makers:

the interest-rate differential between TIPS and conventional US

Treasury bonds is what borrowers are willing to give up in order

to avoid inflation risk. Therefore, changes in this differential

are usually taken to indicate that market expectations about inflation

over the term of the bonds have changed. (Also see inflation derivatives).

The interest

payments from these securities are taxed for federal income tax

purposes in the year payments are received (payments are semi-annual,

or every six months). The inflation adjustment credited to the

bonds is also taxable each year. This tax treatment means that

even though these bonds are intended to protect the holder from

inflation, the cash flows generated by the bonds are actually

inversely related to inflation until the bond matures. For example,

during a period of no inflation, the cash flows will be exactly

the same as for a normal bond, and the holder will receive the

coupon payment minus the taxes on the coupon payment. During a

period of high inflation, the holder will receive the same equivalent

cash flow (in purchasing power terms), and will then have to pay

additional taxes on the inflation adjusted principal. The details

of this tax treatment can have unexpected repercussions. (See

tax on the inflation tax.)

Created

by the Financial Industry

STRIPS

Separate

Trading of Registered Interest and Principal Securities (or

STRIPS) are T-Notes,

T-Bonds and TIPS whose interest and principal portions of the

security have been separated, or "stripped"; these may then be

sold separately (in units of $1000 face value) in the secondary

market. The name derives from the notional practice of literally

tearing the interest coupons off (paper) securities.

The government

does not directly issue STRIPS; they are formed by investment

banks or brokerage firms, but the government does register STRIPS

in its book-entry system. They cannot be bought through TreasuryDirect,

but only through a broker.

Nonmarketable

Securities

Savings

bond

Introduction

Savings

bonds are treasury securities for individual investors. US

Savings Bonds are a registered, non-callable bond issued by the

U.S. Government, and are backed by its full faith and credit.

About one in six Americans - more than 50 million individuals

- have together invested more than $200 billion in savings bonds.

However, all savings bond investments together cover only a minor

portion - less than 3% - of the U.S. public debt.

Savings bonds

have traditionally been issued as paper, or definitive, bonds.

In October 2002 the treasury also began to offer electronic, or

book, savings bonds through its online service TreasuryDirect.

As of 2004, about a quarter of new savings bond investments are

now made electronically.

There is no

active secondary market for Savings Bonds (but they can be transferred

if the taxes due on the accrued interest are paid). After a one-year

holding period they can be redeemed with the Treasury at any time,

making them very liquid. Since they are registered securities,

possession of a savings bond is of no legal consequence; ownership

is determined by the names in the Treasury's records, which are

also printed on paper savings bonds. Consequently, savings bonds

can be replaced if lost or destroyed.

Savings bonds

do not have coupons. Interest payments are compounded or accrued,

which means they are added to the value of the bond and paid out

only upon the bond's redemption. Unlike other treasury securities,

income from these interest payments does not have to be reported

to the IRS as income until the bonds are cashed, which makes savings

bonds tax-deferred investments. Savings bonds redeemed prior to

five years forfeit the most recent three months' interest.

The treasury

first offered the predecessor to savings bonds, called "baby bonds,"

in March, 1935. The bonds were issued in denominations from $25

to $1,000. They were sold at 75 percent of face value, and accrued

interest at the rate of 2.9% per year, compounded semiannually

when held for their ten-year maturity period.

EE

Bond

Series EE

savings bonds were introduced in 1980 to replace the series E

bond. Paper EE bonds are sold at a 50 percent discount to their

face value (from $50 to $10,000), and are guaranteed to be worth

at least face value at "original maturity", which varies from

8 years to (presently) 20 years depending on issue date. Electronic

EE bonds sold through TreasuryDirect are sold at face value ($25

and up); however, they are guaranteed to be worth at least double

their face value at original maturity, so the difference is nominal.

EE Bond interest rates vary depending on issue date, and for older

bonds, yields on other Treasury securities. In May 2005, EE bonds

were assigned a fixed rate at the time of purchase. The rate is

currently 3.0% (as of January 2008). Series EE bonds issued in

May 1997 or later earn interest every month, compounded twice

per year, until they reach "final maturity" after 30 years; earlier

EE bonds vary in interest accrual, but have the same 30-year final

maturity. The interest on series EE bonds purchased since 1989

is exempt from federal and state taxes if it is used for education

expenses, so long as the expenses are incurred in the same year

as the bonds are redeemed. A buyer should beware though that there

are very specific requirements for the bonds to be tax free and

thus should consult the tax code before purchasing as college

savings.

HH

Bond

Series HH

savings bonds originally sold in denominations from $500 to $10,000.

Series E and EE savings bonds were able to be exchanged for them.

The Series HH bonds pay interest semiannually and mature in twenty

years. Series H Bonds mature in 30 years. Federal income tax on

these bonds can be deferred until the bonds are sold or mature.

These bonds have not been available for purchase from the treasury,

or via exchange of other bonds, since September 1, 2004. [1]

I

Bond

Series I Bonds

were introduced in September 1998. They are sold at face value

($50 to $10,000 for paper bonds, $25 and up for electronic bonds)

and grow in value with inflation-indexed earnings (similar to

TIPS) for up to 30 years. I Bonds gain interest once a month,

with interest being compounded twice per year. The composite interest

rate has two components: a guaranteed fixed rate, which does not

change over the 30 year period; and a semiannual inflation rate,

which is adjusted twice per year. Even in times of deflation,

the composite interest rate is guaranteed never to go below zero,

meaning an I Bond's redemption value can never go down. The significant

differences between series I bonds and TIPS are that I bonds retain

all interest to compound inside the bond, are tax-deferred, and

are protected from loss of value, while TIPS pay out a semiannual

coupon, have a somewhat complex tax treatment, can lose value,

and generally have a higher fixed rate.

Patriot

Bonds

Since December

10, 2001, Series EE savings bonds purchased directly through financial

institutions have been printed with the words "Patriot Bond" on

them. Otherwise, the Patriot bond looks the same as the Series

EE Bond, and Patriot bonds are used for financing general government

debt, and not earmarked for any specific purpose. Bonds purchased

from employers are not inscribed with the Patriot bond notation.

Zero-Percent

Certificate of Indebtedness

The "Certificate

of Indebtedness" is a Treasury security that does not earn any

interest and has no fixed maturity. It can only be held in a TreasuryDirect

account and bought or sold directly though the Treasury. Purchases

and redemptions can be made at any time by transfers to or from

a bank checking account, or by direct deposit of salary via payroll

deduction. It is a place to store proceeds of coupon payments,

matured securities, and small contributions until the time when

the account holder is willing and able to buy a marketable Treasury

security or a savings bond (for instance, to save up small amounts

until the minimum purchase is reached). Many TreasuryDirect users

have interest-bearing checking accounts and use them as their

temporary holding place, but the C-of-I is more convenient in

cases where the checking account does not earn interest.

If you want

to reinvest a maturing TreasuryDirect T-Bill security, you should

specify that the maturing value be placed in your C-of-I account.

Then you can buy a new T-Bill that uses most of that money - the

remainder can be transferred to a bank account. The redemption

and the repurchase will occur on the same Thursday.

External

links

- Legacy TreasuryDirect:

- Electronic Services for Legacy TreasuryDirect Treasury Bills, Notes

and Bonds

- Bureau of the Public Debt : US Savings Bonds Online

- Major Foreign Holders of

Treasury Bonds

- Bureau of

the Public Debt: Series A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, J, and K Savings

Bonds and Savings Notes.

- Features and Risks of Treasury Inflation Protection Securities

- All About TIPS

|