Types

of stock

Stock typically

takes the form of shares of common stock (or voting shares). As

a unit of ownership, common stock typically carries voting rights

that can be exercised in corporate decisions. Preferred stock

differs from common stock in that it typically does not carry

voting rights but is legally entitled to receive a certain level

of dividend payments before any dividends can be issued to other

shareholders. [1] [2]

Convertible preferred stock is preferred stock that includes an

option for the holder to convert the preferred shares into a fixed

number of common shares, usually anytime after a predetermined

date. Shares of such stock are called "convertible preferred shares"

(or "convertible preference shares" in the United Kingdom).

Although there

is a great deal of commonality between the stocks of different

companies, each new equity issue can have legal clauses attached

to it that make it dynamically different from the more general

cases. Some shares of common stock may be issued without the typical

voting rights being included, for instance, or some shares may

have special rights unique to them and issued only to certain

parties. These case-by-case variations in the specific form of

stock issuance are beyond the scope of this article, except to

note that not all equity shares are the same. [1]

[2]

Stock

derivatives

-

A stock derivative

is any financial instrument which has a value that is dependent

on the price of the underlying stock. Futures and options are

the main types of derivatives on stocks. The underlying security

may be a stock index or an individual firm's stock, e.g. single-stock

futures.

Stock futures

are contracts where the buyer is long, i.e., takes on the obligation

to buy on the contract maturity date, and the seller is short,

i.e., takes on the obligation to sell. Stock index futures are

generally not delivered in the usual manner, but by cash settlement.

A stock option

is a class of option. Specifically, a call option is the right

(not obligation) to buy stock in the future at a fixed

price and a put option is the right (not obligation) to

sell stock in the future at a fixed price. Thus, the value of

a stock option changes in reaction to the underlying stock of

which it is a derivative. The most popular method of valuing stock

options is the Black Scholes model.[3]

Apart from call options granted to employees, most stock options

are transferable.

History

During Roman

times, the empire contracted out many of its services to private

groups called publicani. Shares in publicani were called "socii"

(for large cooperatives) and "particulae" which were analogous

to today's Over-The-Counter shares of small companies. Though

the records available for this time are incomplete, Edward Chancellor

states in his book Devil Take the Hindmost that there is

some evidence that a speculation in these shares became increasingly

widespread and that perhaps the first ever speculative bubble

in "stocks" occurred.

The first

company to issue shares of stock after the Middle Ages was the

Dutch East India Company in 1606. The innovation of joint ownership

made a great deal of Europe's economic growth possible following

the Middle Ages. The technique of pooling capital to finance the

building of ships, for example, made the Netherlands a maritime

superpower. Before adoption of the joint-stock corporation, an

expensive venture such as the building of a merchant ship could

be undertaken only by governments or by very wealthy individuals

or families.

Economic Historians

find the Dutch stock market of the 1600s particularly interesting:

there is clear documentation of the use of stock futures, stock

options, short selling, the use of credit to purchase shares,

a speculative bubble that crashed in 1695, and a change in fashion

that unfolded and reverted in time with the market (in this case

it was headdresses instead of hemlines). Dr. Edward Stringham

also noted that the uses of practices such as short selling continued

to occur during this time despite the government passing laws

against it. This is unusual because it shows individual parties

fulfilling contracts that were not legally enforceable and where

the parties involved could incur a loss. Stringham argues that

this shows that contracts can be created and enforced without

state sanction or, in this case, in spite of laws to the contrary.[4][5]

Shareholder

A shareholder

(or stockholder) is an individual or company (including

a corporation) that legally owns one or more shares of stock in

a joint stock company. Companies listed at the stock market are

expected to strive to enhance shareholder value.

Shareholders

are granted special privileges depending on the class of stock,

including the right to vote (usually one vote per share owned)

on matters such as elections to the board of directors, the right

to share in distributions of the company's income, the right to

purchase new shares issued by the company, and the right to a

company's assets during a liquidation of the company. However,

shareholder's rights to a company's assets are subordinate to

the rights of the company's creditors. This means that shareholders

typically receive nothing if a company is liquidated after bankruptcy

(if the company had had enough to pay its creditors, it would

not have entered bankruptcy), although a stock may have value

after a bankruptcy if there is the possibility that the debts

of the company will be restructured.

Shareholders

are considered by some to be a partial subset of stakeholders,

which may include anyone who has a direct or indirect equity interest

in the business entity or someone with even a non-pecuniary interest

in a non-profit organization. Thus it might be common to call

volunteer contributors to an association stakeholders, even though

they are not shareholders.

Although directors

and officers of a company are bound by fiduciary duties to act

in the best interest of the shareholders, the shareholders themselves

normally do not have such duties towards each other.

However, in

a few unusual cases, some courts have been willing to imply such

a duty between shareholders. For example, in California, majority

shareholders of closely held corporations have a duty to not destroy

the value of the shares held by minority shareholders. [6][7]

The largest

shareholders (in terms of percentages of companies owned) are

often mutual funds, and especially passively managed exchange-traded

funds.

Application

The owners

of a company may want additional capital to invest in new projects

within the company. They may also simply wish to reduce their

holding, freeing up capital for their own private use.

By selling

shares they can sell part or all of the company to many part-owners.

The purchase of one share entitles the owner of that share to

literally share in the ownership of the company, a fraction of

the decision-making power, and potentially a fraction of the profits,

which the company may issue as dividends.

In the common

case of a publicly traded corporation, where there may be thousands

of shareholders, it is impractical to have all of them making

the daily decisions required to run a company. Thus, the shareholders

will use their shares as votes in the election of members of the

board of directors of the company.

In a typical

case, each share constitutes one vote. Corporations may, however,

issue different classes of shares, which may have different voting

rights. Owning the majority of the shares allows other shareholders

to be out-voted - effective control rests with the majority shareholder

(or shareholders acting in concert). In this way the original

owners of the company often still have control of the company.

Shareholder

rights

Although ownership

of 51% of shares does result in 51% ownership of a company, it

does not give the shareholder the right to use a company's building,

equipment, materials, or other property. This is because the company

is considered a legal person, thus it owns all its assets itself.

This is important in areas such as insurance, which must be in

the name of the company and not the main shareholder.

In most countries,

including the United States, boards of directors and company managers

have a fiduciary responsibility to run the company in the interests

of its stockholders. Nonetheless, as Martin Whitman writes:

- "...it

can safely be stated that there does not exist any publicly

traded company where management works exclusively in the best

interests of OPMI [Outside Passive Minority Investor] stockholders.

Instead, there are both "communities of interest" and "conflicts

of interest" between stockholders (principal) and management

(agent). This conflict is referred to as the principal/agent

problem. It would be naive to think that any management would

forgo management compensation, and management entrenchment,

just because some of these management privileges might be perceived

as giving rise to a conflict of interest with OPMIs."'[8]

Even though

the board of directors runs the company, the shareholder has some

impact on the company's policy, as the shareholders elect the

board of directors. Each shareholder typically has a percentage

of votes equal to the percentage of shares he or she owns. So

as long as the shareholders agree that the management (agent)

are performing poorly they can elect a new board of directors

which can then hire a new management team. In practice, however,

genuinely contested board elections are rare. Board candidates

are usually nominated by insiders or by the board of the directors

themselves, and a considerable amount of stock is held and voted

by insiders.

Owning shares

does not mean responsibility for liabilities. If a company goes

broke and has to default on loans, the shareholders are not liable

in any way. However, all money obtained by converting assets into

cash will be used to repay loans and other debts first, so that

shareholders cannot receive any money unless and until creditors

have been paid (most often the shareholders end up with nothing).

Means

of financing

Financing

a company through the sale of stock in a company is known as equity

financing. Alternatively, debt financing (for example issuing

bonds) can be done to avoid giving up shares of ownership of the

company. Unofficial financing known as trade financing usually

provides the major part of a company's working capital (day-to-day

operational needs). Trade financing is provided by vendors and

suppliers who sell their products to the company at short-term,

unsecured credit terms, usually 30 days. Equity and debt financing

are usually used for longer-term investment projects such as investments

in a new factory or a new foreign market. Customer provided financing

exists when a customer pays for services before they are delivered,

e.g. subscriptions and insurance.

Trading

A stock exchange is an organization that provides

a marketplace for either physical or virtual trading shares, bonds

and warrants and other financial products where investors (represented

by stock brokers) may buy and sell shares of a wide range of companies.

A company will usually list its shares by meeting and maintaining

the listing requirements of a particular stock exchange and the

different. In the United States, through the inter-market quotation

system, stocks listed on one exchange can also be bought or sold

on several other exchanges, including relatively new so-called

ECNs (Electronic Communication Networks like Archipelago or Instinet).

Stocks used

to be broadly grouped into NYSE-listed

and NASDAQ-listed stocks. Until a few

years ago there was a law in the USA that NYSE listed stocks were

not allowed to be listed on the NASDAQ or vice versa.

Many large

foreign companies choose to list on a U.S. exchange as well as

an exchange in their home country in order to broaden their investor

base. These companies have then to ship a certain amount of shares

to a bank in the US (a certain percentage of their principal)

and put it in the safe of the bank. Then the bank where they deposited

the shares can issue a certain amount of so-called American Depositary

Shares, short ADS (singular). If someone buys now a certain amount

of ADSs the bank where the shares are deposited issues an American

Depository Receipt (ADR) for the buyer of the ADSs.

Likewise,

many large U.S. companies list themselves at foreign exchanges

to raise capital abroad.

Arbitrage

trading

Although it

makes sense for some companies to raise capital by offering stock

on more than one exchange, a keen investor with access to information

about such discrepancies could invest in expectation of their

eventual convergence, known as an arbitrage trade. In today's

era of electronic trading, these discrepancies, if they exist,

are both shorter-lived and more quickly acted upon. As such, arbitrage

opportunities disappear quickly due to the efficient nature of

the market.

Buying

There are

various methods of buying and financing stocks. The most common

means is through a stock broker. Whether they are a full service

or discount broker, they arrange the transfer of stock from a

seller to a buyer. Most trades are actually done through brokers

listed with a stock exchange, such as the New York Stock Exchange.

There are

many different stock brokers from which to choose, such as full

service brokers or discount brokers. The full service brokers

usually charge more per trade, but give investment advice or more

personal service; the discount brokers offer little or no investment

advice but charge less for trades. Another type of broker would

be a bank or credit union that may have a deal set up with either

a full service or discount broker.

There are

other ways of buying stock besides through a broker. One way is

directly from the company itself. If at least one share is owned,

most companies will allow the purchase of shares directly from

the company through their investor relations departments. However,

the initial share of stock in the company will have to be obtained

through a regular stock broker. Another way to buy stock in companies

is through Direct Public Offerings which are usually sold by the

company itself. A direct public offering is an initial public

offering in which the stock is purchased directly from the company,

usually without the aid of brokers.

When it comes

to financing a purchase of stocks there are two ways: purchasing

stock with money that is currently in the buyers ownership, or

by buying stock on margin. Buying stock on margin means buying

stock with money borrowed against the stocks in the same account.

These stocks, or collateral, guarantee that the buyer can repay

the loan; otherwise, the stockbroker has the right to sell the

stock (collateral) to repay the borrowed money. He can sell if

the share price drops below the margin requirement, at least 50%

of the value of the stocks in the account. Buying on margin works

the same way as borrowing money to buy a car or a house, using

the car or house as collateral. Moreover, borrowing is not free;

the broker usually charges 8-10% interest.

Selling

Selling stock

is procedurally similar to buying stock. Generally, the investor

wants to buy low and sell high, if not in that order (short selling); although a number of reasons may

induce an investor to sell at a loss, e.g., to avoid further loss.

As with buying

a stock, there is a transaction fee for the broker's efforts in

arranging the transfer of stock from a seller to a buyer. This

fee can be high or low depending on which type of brokerage, full

service or discount, handles the transaction.

After the

transaction has been made, the seller is then entitled to all

of the money. An important part of selling is keeping track of

the earnings. Importantly, on selling the stock, in jurisdictions

that have them, capital gains taxes will have to be paid on the

additional proceeds, if any, that are in excess of the cost basis.

Stock

price fluctuations

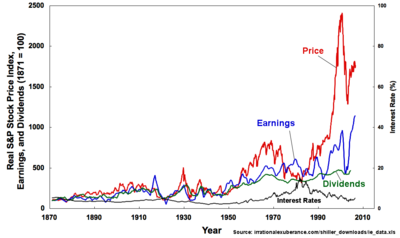

Robert

Shiller's plot of the S&P Composite Real Price Index,

Earnings, Dividends, and Interest Rates, from Irrational

Exuberance, 2d ed.[9]

In the preface to this edition, Shiller warns that "[t]he

stock market has not come down to historical levels: the price-earnings

ratio as I define it in this book is still, at this writing

[2005], in the mid-20s, far higher than the historical average.

… People still place too much confidence in the markets

and have too strong a belief that paying attention to the

gyrations in their investments will someday make them rich,

and so they do not make conservative preparations for possible

bad outcomes."

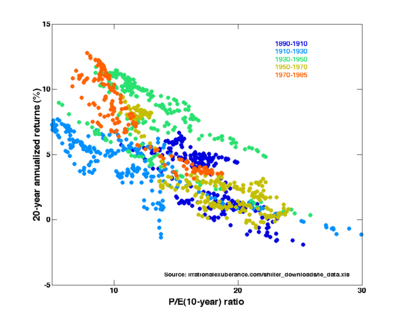

Price-Earnings

ratios as a predictor of twenty-year returns based upon the

plot by Robert Shiller (Figure 10.1[9],

source). The horizontal axis shows the real

price-earnings ratio of the S&P Composite Stock Price

Index as computed in Irrational Exuberance (inflation

adjusted price divided by the prior ten-year mean of inflation-adjusted

earnings). The vertical axis shows the geometric average real

annual return on investing in the S&P Composite Stock

Price Index, reinvesting dividends, and selling twenty years

later. Data from different twenty year periods is color-coded

as shown in the key. See also ten-year returns. Shiller states

that this plot "confirms that long-term investors—investors

who commit their money to an investment for ten full years—did

do well when prices were low relative to earnings at the beginning

of the ten years. Long-term investors would be well advised,

individually, to lower their exposure to the stock market

when it is high, as it has been recently, and get into the

market when it is low."[9]

The price

of a stock fluctuates fundamentally due to the theory of supply

and demand. Like all commodities in the market, the price of a

stock is directly proportional to the demand. However, there are

many factors on the basis of which the demand for a particular

stock may increase or decrease. These factors are studied using

methods of fundamental analysis and technical analysis to predict

the changes in the stock price. A recent study shows that customer

satisfaction, as measured by the American Customer Satisfaction

Index (ACSI), is significantly correlated to the stock market

value. Stock price is also changed based on the forecast for the

company and whether their profits are expected to increase or

decrease.

Notes

- "Stock Basics", Investor Guide.com.

-

Zvi Bodie, Alex Kane, Alan J. Marcus, Investments, 7th

Ed., p. 26–53.

- http://www.tradingtoday.com/black-scholes

- http://www.sjsu.edu/depts/economics/faculty/stringham/docs/stringham-amsterdam.pdf

- "Devil

Take the Hindmost" by Edward Chancellor.

- Jones

v. H. F. Ahmanson & Co., 1 Cal. 3d)

- http://online.ceb.com/calcases/C3/1C3d93.htm

- Whitman,

2004, 5

- Shiller,

Robert (2005). Irrational

Exuberance (2d ed.). Princeton University

Press. ISBN 0-691-12335-7.

|