In finance,

a futures contract is a standardized contract, traded

on a futures exchange, to buy or sell a certain underlying instrument

at a certain date in the future, at a specified price. The future

date is called the delivery date or final settlement

date. The pre-set price is called the futures price.

The price of the underlying asset on the delivery date is called

the settlement price.

A futures

contract gives the holder the obligation to buy or sell,

which differs from an options contract, which gives the holder

the right, but not the obligation. In other words, the

owner of an options contract may exercise the contract,

but both parties of a "futures contract" must fulfill

the contract on the settlement date. The seller delivers the

commodity to the buyer, or, if it is a cash-settled future,

then cash is transferred from the futures trader who sustained

a loss to the one who made a profit. To exit the commitment

prior to the settlement date, the holder of a futures position

has to offset their position by either selling a long position

or buying back a short position, effectively closing out the

futures position and its contract obligations.

Futures

contracts, or simply futures, are exchange traded

derivatives. The exchange's clearinghouse acts as counterparty

on all contracts, sets margin requirements, etc.

Futures

vs. Forwards

While futures

and forward contracts are both a contract to deliver a commodity

on a future date at a prearranged price, they are different

in several respects:

- Forwards

transact only when purchased and on the settlement date. Futures,

on the other hand, are rebalanced, or "marked to market,"

every day to the daily spot price of a forward with the same

agreed-upon delivery price and underlying asset.

- The

fact that forwards are not rebalanced daily means that,

due to movements in the price of the underlying asset,

a large differential can build up between the forward's

delivery price and the settlement price.

- This

means that one party will incur a big loss at the

time of delivery (assuming they must transact at the

underlying's spot price to facilitate receipt/delivery).

- This

in turn creates a credit risk. More generally, the

risk of a forward contract is that the supplier will

be unable to deliver the required commodity, or that

the buyer will be unable to pay for it on the delivery

day.

- The

rebalancing of futures eliminates much of this credit

risk by forcing the holders to update daily to the price

of an equivalent forward purchased that day. This means

that there will usually be very little additional money

due on the final day to settle the futures contract.

- In

addition, the daily futures-settlement failure risk is

borne by an exchange, rather than an individual party,

limiting credit risk in futures.

- Example

for a futures contract with a $100 price: Let's say that

on day 50, a forward with a $100 delivery price (on the

same underlying asset as the future) costs $88. On day

51, that forward costs $90. This means that the mark-to-market

would require the holder of one side of the future to

pay $2 on day 51 to track the changes of the forward price.

This money goes, via margin accounts, to the holder of

the other side of the future. (A forward-holder, however,

would pay nothing until settlement on the final day, potentially

building up a large balance. So, except for tiny effects

of convexity bias or possible allowance for credit risk,

futures and forwards with equal delivery prices result

in the same total loss or gain, but holders of futures

experience that loss/gain in daily increments which track

the forward's daily price changes, while the forward's

spot price converges to the settlement price.)

- Futures

are always traded on an exchange, whereas forwards always

trade over-the-counter, or can simply be a signed contract

between two parties.

- Futures

are highly standardised, whereas some forwards are unique.

- In the

case of physical delivery, the forward contract specifies

to whom to make the delivery. The counterparty for delivery

on a futures contract is chosen by the clearinghouse.

Some exchanges

tolerate 'nonconvergence', the failure of futures contracts

and the value of the physical commodities they represent to

reach the same value on 'contract settlement' day at the designated

delivery points. An example of this is the CBOT (Chicago Board

of Trade)Soft Red Winter wheat (SRW) futures. SRW futures have

settled more than 20¢ apart on settlement day and as much as

$1.00 difference between settlement days. Only a few participants

holding CBOT SRW futures contracts are qualified by the CBOT

to make or receive delivery of commodities to settle futures

contracts. Therefore, it's impossible for almost any individual

producer to 'hedge' efficiently when relying on the final settlement

of a futures contract for SRW. The trend is the CBOT continuing

to restrict those entities who can actually participate in settling

contracts with commodity to only those that can ship or receive

large quantities of railroad cars and multiple barges at a few

selected sites. The CFTC (Commodity Futures Trading Commission

- a regulatory agency headed by a political appointee), which

has oversight of the futures market, has made no comment as

to why this trend is allowed to continue since economic theory

and CBOT publications maintain that convergence of contracts

with the price of the underlying commodity they represent is

the basis of integrity for a futures market. It follows that

the function of 'price discovery', the ability of the markets

to discern the appropriate value of a commodity reflecting current

conditions, is degraded in relation to the discrepancy in price

and the inability of producers to enforce contracts with the

commodities they represent.

Standardization

Futures

contracts ensure their liquidity by being highly

standardized, usually by specifying:

- The underlying

asset or instrument. This could be anything from a barrel

of crude oil to a short term interest rate.

- The type

of settlement, either cash settlement or physical settlement.

- The amount

and units of the underlying asset per contract. This can be

the notional amount of bonds, a fixed number of barrels of

oil, units of foreign currency, the notional amount of the

deposit over which the short term interest rate is traded,

etc.

- The currency

in which the futures contract is quoted.

- The grade

of the deliverable. In the case of bonds, this specifies which

bonds can be delivered. In the case of physical commodities,

this specifies not only the quality of the underlying goods

but also the manner and location of delivery. For example,

the NYMEX Light Sweet Crude Oil contract specifies

the acceptable sulfur content and API specific gravity, as

well as the location where delivery must be made.

- The delivery

month.

- The last

trading date.

- Other

details such as the commodity tick, the minimum permissible

price fluctuation.

Margin

To minimize

credit risk to the exchange, traders must post margin or a performance

bond, typically 5%-15% of the contract's value.

Margin requirements

are waived or reduced in some cases for hedgers who have physical

ownership of the covered commodity or spread traders who have

offsetting contracts balancing the position.

Initial

margin is paid by both buyer and seller. It represents the

loss on that contract, as determined by historical price changes,

that is not likely to be exceeded on a usual day's trading.

A futures

account is marked to market daily. If the margin drops below

the margin maintenance requirement established by the exchange

listing the futures, a margin call will be issued to bring the

account back up to the required level.

Margin-equity

ratio is a term used by speculators, representing the amount

of their trading capital that is being held as margin at any

particular time. The low margin requirements of futures results

in substantial leverage of the investment. However, the exchanges

require a minimum amount that varies depending on the contract

and the trader. The broker may set the requirement higher, but

may not set it lower. A trader, of course, can set it above

that, if he doesn't want to be subject to margin calls.

Return

on margin (ROM) is often used to judge performance because

it represents the gain or loss compared to the exchange™s perceived

risk as reflected in required margin. ROM may be calculated

(realized return) / (initial margin). The Annualized ROM is

equal to (ROM+1)(year/trade_duration)-1. For example

if a trader earns 10% on margin in two months, that would be

about 77% annualized.

Settlement

Settlement

is the act of consummating the contract, and can be done in

one of two ways, as specified per type of futures contract:

- Physical

delivery - the amount specified of the underlying asset

of the contract is delivered by the seller of the contract

to the exchange, and by the exchange to the buyers of the

contract. Physical delivery is common with commodities and

bonds. In practice, it occurs only on a minority of contracts.

Most are cancelled out by purchasing a covering position -

that is, buying a contract to cancel out an earlier sale (covering

a short), or selling a contract to liquidate an earlier purchase

(covering a long). The Nymex crude futures contract uses this

method of settlement upon expiration.

- Cash

settlement - a cash payment is made based on the underlying

reference rate, such as a short term interest rate index such

as Euribor, or the closing value of a stock market index.

A futures contract might also opt to settle against an index

based on trade in a related spot market. Ice Brent futures

use this method.

- Expiry

is the time when the final prices of the future is determined.

For many equity index and interest rate futures contracts

(as well as for most equity options), this happens on the

third Friday of certain trading month. On this day the t+1

futures contract becomes the t futures contract. For

example, for most CME and CBOT contracts, at the expiry on

December, the March futures become the nearest contract. This

is an exciting time for arbitrage desks, as they will try

to make rapid gains during the short period (normally 30 minutes)

where the final prices are averaged from. At this moment the

futures and the underlying assets are extremely liquid and

any mispricing between an index and an underlying asset is

quickly traded by arbitrageurs. At this moment also, the increase

in volume is caused by traders rolling over positions to the

next contract or, in the case of equity index futures, purchasing

underlying components of those indexes to hedge against current

index positions. On the expiry date, a European equity arbitrage

trading desk in London or Frankfurt will see positions expire

in as many as eight major markets almost every half an hour.

Pricing

The situation

where the price of a commodity for future delivery is higher

than the spot price, or where a far future delivery price is

higher than a nearer future delivery, is known as contango.

The reverse, where the price of a commodity for future delivery

is lower than the spot price, or where a far future delivery

price is lower than a nearer future delivery, is known as backwardation.

When the

deliverable asset exists in plentiful supply, or may be freely

created, then the price of a future is determined via arbitrage

arguments. The forward price represents the expected future

value of the underlying discounted at the risk free rate—as

any deviation from the theoretical price will afford investors

a riskless profit opportunity and should be arbitraged away;

see rational pricing of futures.

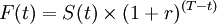

Thus, for

a simple, non-dividend paying asset, the value of the future/forward,

F(t), will be found by compounding the present value

S(t) at time t to maturity T by the rate

of risk-free return r.

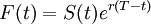

or, with

continuous compounding

This relationship

may be modified for storage costs, dividends, dividend yields,

and convenience yields.

In a perfect

market the relationship between futures and spot prices depends

only on the above variables; in practice there are various market

imperfections (transaction costs, differential borrowing and

lending rates, restrictions on short selling) that prevent complete

arbitrage. Thus, the futures price in fact varies within arbitrage

boundaries around the theoretical price.

The above

relationship, therefore, is typical for stock index futures,

treasury bond futures, and futures on physical commodities when

they are in supply (e.g. on corn after the harvest). However,

when the deliverable commodity is not in plentiful supply or

when it does not yet exist, for example on wheat before the

harvest or on Eurodollar Futures or Federal funds rate futures

(in which the supposed underlying instrument is to be created

upon the delivery date), the futures price cannot be fixed by

arbitrage. In this scenario there is only one force setting

the price, which is simple supply and demand for the future

asset, as expressed by supply and demand for the futures contract.

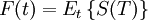

In a deep

and liquid market, this supply and demand would be expected

to balance out at a price which represents an unbiased expectation

of the future price of the actual asset and so be given by the

simple relationship

.

.

In fact,

this relationship will hold in a no-arbitrage setting when we

take expectations with respect to the risk-neutral probability.

In other words: a futures price is martingale with respect to

the risk-neutral probability.

With this

pricing rule, a speculator is expected to break even when the

futures market fairly prices the deliverable commodity.

In a shallow

and illiquid market, or in a market in which large quantities

of the deliverable asset have been deliberately withheld from

market participants (an illegal action known as cornering the

market), the market clearing price for the future may still

represent the balance between supply and demand but the relationship

between this price and the expected future price of the asset

can break down.

Futures

contracts and exchanges

There are

many different kinds of futures contracts, reflecting the many

different kinds of tradable assets of which they are derivatives.

Trading

on commodities began in Japan in the 18th century with the trading

of rice and silk, and similarly in Holland with tulip bulbs.

Trading in the US began in the mid 19th century, when central

grain markets were established and a marketplace was created

for farmers to bring their commodities and sell them either

for immediate delivery (also called spot or cash market) or

for forward delivery. These forward contracts were private contracts

between buyers and sellers and became the forerunner to today's

exchange-traded futures contracts. Although contract trading

began with traditional commodities such grains, meat and livestock,

exchange trading has expanded to include metals, energy, currency

and currency indexes, equities and equity indexes, government

interest rates and private interest rates.

Contracts

on financial instruments was introduced in the 1970s by the

Chicago Mercantile Exchange(CME) and

these instruments became hugely successful and quickly overtook

commodities futures in terms of trading volume and global accessibility

to the markets. This innovation led to the introduction of many

new futures exchanges worldwide, such as the London International

Financial Futures Exchange in 1982 (now Euronext.liffe), Deutsche

Terminbase (now Eurex) and the Tokyo Commodity Exchange (TOCOM).

Today, there are more than 75 futures and futures options exchanges

worldwide trading to include:

- CME Group

(formerly CBOT and CME) -- Currencies, Various Interest Rate

derivatives (including US Bonds); Agricultural (Corn, Soybeans,

Soy Products, Wheat, Pork, Cattle, Butter, Milk); Index (Dow

Jones Industrial Average); Metals (Gold, Silver), Index (NASDAQ,

S&P, etc)

- ICE Futures

- the International Petroleum Exchange trades energy including

crude oil, heating oil, natural gas and unleaded gas and merged

with IntercontinentalExchange(ICE)to form ICE Futures.

- Euronext.liffe

- South

African Futures Exchange - SAFEX

- Sydney

Futures Exchange

- London

Commodity Exchange - softs: grains and meats. Inactive market

in Baltic Exchange shipping.

- Tokyo

Stock Exchange TSE (JGB Futures, TOPIX Futures)

- Tokyo

Commodity Exchange TOCOM

- Tokyo

Financial Exchange TFX (Euroyen Futures, OverNight CallRate

Futures, SpotNext RepoRate Futures)

- Osaka

Securities Exchange OSE (Nikkei Futures, RNP Futures)

- London

Metal Exchange - metals: copper, aluminium, lead, zinc, nickel

and tin.

- New York

Board of Trade - softs: cocoa, coffee, cotton, orange juice,

sugar

- New York

Mercantile Exchange - energy and metals: crude oil, gasoline,

heating oil, natural gas, coal, propane, gold, silver, platinum,

copper, aluminum and palladium

- Dubai

Mercantile Exchange

- Futures

exchange

- Singapore

International Monetary Exchange (SIMEX)

- Futures

on many Single-stock futures

Who

trades futures?

Futures

traders are traditionally placed in one of two groups: hedgers,

who have an interest in the underlying commodity and are seeking

to hedge out the risk of price changes; and speculators,

who seek to make a profit by predicting market moves and buying

a commodity "on paper" for which they have no practical use.

Hedgers

typically include producers and consumers of a commodity.

For example,

in traditional commodities markets, farmers often sell futures

contracts for the crops and livestock they produce to guarantee

a certain price, making it easier for them to plan. Similarly,

livestock producers often purchase futures to cover their feed

costs, so that they can plan on a fixed cost for feed. In modern

(financial) markets, "producers" of interest rate swaps or equity

derivative products will use financial futures or equity index

futures to reduce or remove the risk on the swap.

The social

utility of futures markets is considered to be mainly in the

transfer of risk, and increase liquidity between traders with

different risk and time preferences, from a hedger to a speculator

for example.

Options

on futures

In many

cases, options are traded

on futures. A put is the option to sell a futures contract,

and a call is the option to buy a futures contract. For both,

the option strike price is the specified futures price at which

the future is traded if the option is exercised. See the Black

model, which is the most popular method for pricing these option

contracts..

Futures

Contract Regulations

All futures

transactions in the United States are regulated by the Commodity

Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), an independent agency of

the United States Government. The Commission has the right to

hand out fines and other punishments for an individual or company

who breaks any rule. Although by law the commission regulates

all transactions, each exchange can have its own rule, and under

contract can fine companies for different things or extend the

fine that the CFTC hands out.

The CFTC

publishes weekly reports containing details of the open interest

of market participants for each market-segment, which has more

than 20 participants. These reports are released every Friday

(including data from the previous Tuesday) and contain data

on open interest split by reportable and non-reportable open

interest as well as commercial and non-commercial open interest.

This type of report is referred to as 'Commitments-Of-Traders'-Report,

COT-Report or simply COTR.

References

- John

C. Hull, Options, Futures, and Other Derivatives, 6th

edition 2006, Prentice-Hall

- Keith

Redhead, (31 Oct 1996), Financial Derivatives: An Introduction

to Futures, Forwards, Options and Swaps, Prentice-Hall

- Abraham

Lioui & Patrice Poncet, (March 30, 2005), Dynamic Asset

Allocation with Forwards and Futures, Springer

- Valdez,

Steven, . An Introduction To Global Financial Markets.

Macmillan Press Ltd. (ISBN 0-333-76447-1)

- Arditti,

Fred D., 19nn. Derivatives: A Comprehensive Resource for

Options, Futures, Interest Rate Swaps, and Mortgage Securities.

Harvard Business School Press. ISBN 0-87584-560-6.

Futures

Exchanges & Regulators