The Elliott

wave principle is a form of technical analysis that attempts to forecast

trends in the financial markets and other collective activities.

It is named after Ralph Nelson Elliott (1871-1948), an accountant

who developed the concept in the 1930s: he proposed that market

prices unfold in specific patterns, which practitioners today

call Elliott waves. Elliott published his views of market behavior

in the book The Wave Principle (1938), in a series of articles

in Financial World magazine in 1939, and most fully in

his final major work, Nature™s Laws “ The Secret of the Universe

(1946).[1]

Elliott argued that because humans are themselves rhythmical,

their activities and decisions could be predicted in rhythms,

too. Critics argue the theory is unprovable and inconsistent with

the efficient market hypothesis and at

odds with modern social science.

Overall

design

The wave principle

posits that collective investor psychology (or crowd psychology)

moves from optimism to pessimism and back again. These swings

create patterns, as evidenced in the price movements of a market

at every degree of trend.

From R.N.

Elliott's essay, "The Basis of the Wave Principle," October

1940.

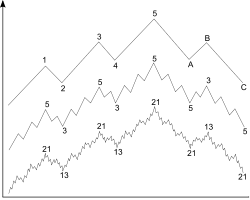

Elliott's

model says that market prices alternate between five waves and

three waves at all degrees of trend, as the illustration shows.

As these waves develop, the larger price patterns unfold in a

self-similar fractal geometry. Within the dominant trend, waves

1, 3, and 5 are "motive" waves, and each motive wave itself subdivides

in five waves. Waves 2 and 4 are "corrective" waves, and subdivide

in three waves. In a bear market the dominant trend is downward,

so the pattern is reversed five waves down and three up. Motive

waves always move with the trend, while corrective waves move

against it.

Degree

The patterns

link to form five and three-wave structures of increasing size

or "degree." Note the lowest of the three idealized cycles. In

the first small five-wave sequence, waves 1, 3 and 5 are motive,

while waves 2 and 4 are corrective. This signals that the movement

of one larger degree is upward. It also signals the start of the

first small three-wave corrective sequence. After the initial

five waves up and three waves down, the sequence begins again

and the self-similar fractal geometry begins to unfold. The completed

motive pattern includes 89 waves, followed by a completed corrective

pattern of 55 waves.[2]

Each degree

of the pattern in a financial market has a name. Practitioners

use symbols for each wave to indicate both function and degree

numbers for motive waves, letters for corrective waves (shown

in the highest of the three idealized cycles). Degrees are relative;

they are defined by form, not by absolute size or duration. Waves

of the same degree may be of very different size and/or duration.[2]

The classification

of a wave at any particular degree can vary, though practitioners

generally agree on the standard order of degrees (approximate

durations given):

- Grand

supercycle: multi-decade to multi-century

-

- Supercycle:

a few years to a few decades

-

- Cycle:

one year to a few years

-

- Primary:

a few months to a couple of years

-

- Intermediate:

weeks to months

-

-

-

-

Behavioral

characteristics and wave "signature"

Elliott Wave

analysts (or "Elliotticians") hold that it is not necessary to

look at a price chart to judge where a market is in its wave pattern.

Each wave has its own "signature" which often reflects the psychology

of the moment. Understanding how and why the waves develop is

key to the application of the Wave Principle; that understanding

includes recognizing the characteristics described below.[2]

These wave

characteristics assume a bull market in equities. The characteristics

apply in reverse in bear markets.

| Five

wave pattern (dominant trend) |

Three

wave pattern (corrective trend) |

| Wave

1: Wave one is rarely obvious at its inception. When the

first wave of a new bull market begins, the fundamental news

is almost universally negative. The previous trend is considered

still strongly in force. Fundamental analysts continue to

revise their earnings estimates lower; the economy probably

does not look strong. Sentiment surveys are decidedly bearish,

put options are in vogue, and implied volatility in the options

market is high. Volume might increase a bit as prices rise,

but not by enough to alert many technical analysts. |

Wave

A: Corrections are typically harder to identify than impulse

moves. In wave A of a bear market, the fundamental news is

usually still positive. Most analysts see the drop as a correction

in a still-active bull market. Some technical indicators that

accompany wave A include increased volume, rising implied

volatility in the options markets and possibly a turn higher

in open interest in related futures markets. |

| Wave

2: Wave two corrects wave one, but can never extend beyond

the starting point of wave one. Typically, the news is still

bad. As prices retest the prior low, bearish sentiment quickly

builds, and "the crowd" haughtily reminds all that the bear

market is still deeply ensconced. Still, some positive signs

appear for those who are looking: volume should be lower during

wave two than during wave one, prices usually do not retrace

more than 61.8% (see Fibonacci section below) of the wave

one gains, and prices should fall in a three wave pattern. |

Wave

B: Prices reverse higher, which many see as a resumption

of the now long-gone bull market. Those familiar with classical

technical analysis may see the peak as the right shoulder

of a head and shoulders reversal pattern. The volume during

wave B should be lower than in wave A. By this point, fundamentals

are probably no longer improving, but they most likely have

not yet turned negative. |

| Wave

3: Wave three is usually the largest and most powerful

wave in a trend (although some research suggests that in commodity

markets, wave five is the largest). The news is now positive

and fundamental analysts start to raise earnings estimates.

Prices rise quickly, corrections are short-lived and shallow.

Anyone looking to "get in on a pullback" will likely miss

the boat. As wave three starts, the news is probably still

bearish, and most market players remain negative; but by wave

three's midpoint, "the crowd" will often join the new bullish

trend. Wave three often extends wave one by a ratio of 1.618:1. |

Wave

C: Prices move impulsively lower in five waves. Volume

picks up, and by the third leg of wave C, almost everyone

realizes that a bear market is firmly entrenched. Wave C is

typically at least as large as wave A and often extends to

1.618 times wave A or beyond. |

| Wave

4: Wave four is typically clearly corrective. Prices may

meander sideways for an extended period, and wave four typically

retraces less than 38.2% of wave three. Volume is well below

than that of wave three. This is a good place to buy a pull

back if you understand the potential ahead for wave 5. Still,

the most distinguishing feature of fourth waves is that they

often prove very difficult to count. |

|

| Wave

5: Wave five is the final leg in the direction of the

dominant trend. The news is almost universally positive and

everyone is bullish. Unfortunately, this is when many average

investors finally buy in, right before the top. Volume is

lower in wave five than in wave three, and many momentum indicators

start to show divergences (prices reach a new high, the indicator

does not reach a new peak). At the end of a major bull market,

bears may very well be ridiculed (recall how forecasts for

a top in the stock market during 2000 were received). |

Pattern

recognition and fractals

Elliott's

market model relies heavily on looking at price charts. Practitioners

study developing price moves to distinguish the waves and wave

structures, and discern what prices may do next; thus the application

of the wave principle is a form of pattern recognition.

The structures

Elliott described also meet the common definition of a fractal

(self-similar patterns appearing at every degree of trend). Elliott

wave practitioners say that just as naturally-occurring fractals

often expand and grow more complex over time, the model shows

that collective human psychology develops in natural patterns,

via buying and selling decisions reflected in market prices: "It's

as though we are somehow programmed by mathematics. Seashell,

galaxy, snowflake or human: we're all bound by the same order."[3]

Fibonacci

relationships

R. N. Elliott's

analysis of the mathematical properties of waves and patterns

eventually led him to conclude that "The Fibonacci Summation Series

is the basis of The Wave Principle."[1]

Numbers from the Fibonacci sequence surface repeatedly in Elliott

wave structures, including motive waves (1, 3, 5), a single full

cycle (5 up, 3 down = 8 waves), and the completed motive (89 waves)

and corrective (55 waves) patterns. Elliott developed his market

model before he realized that it reflects the Fibonacci sequence.

"When I discovered The Wave Principle action of market trends,

I had never heard of either the Fibonacci Series or the Pythagorean

Diagram."[1]

The Fibonacci

sequence is also closely connected to the Golden ratio (1.618).

Practitioners commonly use this ratio and related ratios to establish

support and resistance levels for market waves, namely the price

points which help define the parameters of a trend.[4]

Finance professor

Roy Batchelor and researcher Richard Ramyar, a former Director

of the United Kingdom Society of Technical Analysts and Head of

UK Asset Management Research at Reuters Lipper, studied whether

Fibonacci ratios appear non-randomly in the stock market, as Elliott's

model predicts. The researchers said the "idea that prices retrace

to a Fibonacci ratio or round fraction of the previous trend clearly

lacks any scientific rationale." They also said "there is no significant

difference between the frequencies with which price and time ratios

occur in cycles in the Dow Jones Industrial Average, and frequencies

which we would expect to occur at random in such a time series."[5]

Robert Prechter

replied to the Batchelor-Ramyar study, saying that it "does not

challenge the validity of any aspect of the Wave Principle...it

supports wave theorists' observations."[6]

The Socionomics Institute also reviewed data in the Batchelor-Ramyar

study, and said this data shows "Fibonacci ratios do occur more

often in the stock market than would be expected in a random environment."'[7]

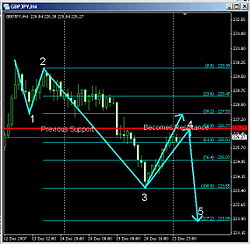

Example

of The Elliott Wave Principle and The Fibonacci Relationship

From sakuragi_indofx,

"Trading never been so easy eh," December 2007.

The GBP/JPY

currency chart gives an example of a fourth wave retracement apparently

halting between the 38.2% and 50.0% Fibonacci retracements of

a completed third wave. The chart also highlights how the Elliott

Wave Prinicple works well with other technical analysis tendencies

as prior support (the bottom of wave-1) acts as resistance to

wave-4. The wave count depicted in the chart would be invalidated

if GBP/JPY moves above the wave-1 low.

After

Elliott

Following

Elliott's death in 1948, other market technicians and financial

professionals continued to use the wave principle and provide

forecasts to investors. Charles Collins, who had published Elliott's

"Wave Principle" and helped introduce Elliott's theory to Wall

Street, ranked Elliott's contributions to technical analysis on

a level with Charles Dow. Hamilton Bolton, founder of The Bank

Credit Analyst, provided wave analysis to a wide readership in

the 1950s and 1960s. Bolton introduced Elliott's wave principle

to A.J. Frost, who provided weekly financial commentary on the

Financial News Network in the 1980s. Frost co-authored Elliott

Wave Principle with Robert Prechter in 1979.

Rediscovery

and current use

Robert Prechter

came across Elliott's works while working as a market technician

at Merrill Lynch. His fame as a forecaster during the bull market

of the 1980s brought the greatest exposure to date to Elliott's

theory, and today Prechter remains the most widely known Elliott

analyst.

Among market

technicians, wave analysis is widely accepted as a component of

their trade. Elliott Wave Theory is among the methods included

on the exam that analysts must pass to earn the Chartered Market

Technician (CMT) designation, the professional accreditation developed

by the Market Technicians Association (MTA).

Robin Wilkin,

Global Head of FX and Commodity Technical Strategy at JPMorgan

Chase, says "the Elliott Wave principle… provides a probability

framework as to when to enter a particular market and where to

get out, whether for a profit or a loss."[8]

Jordan Kotick,

Global Head of Technical Strategy at Barclays Capital and past

President of the Market Technicians Association, has said that

R. N. Elliott's "discovery was well ahead of its time. In fact,

over the last decade or two, many prominent academics have embraced

Elliott’s idea and have been aggressively advocating the existence

of financial market fractals."[9]

One such academic

is the physicist Didier Sornette, visiting professor at the Department

of Earth and Space Science and the Institute of Geophysics and

Planetary Physics at UCLA. A paper he co-authored in 1996 ("Stock

Market Crashes, Precursors and Replicas") said,

-

- "It

is intriguing that the log-periodic structures documented

here bear some similarity with the 'Elliott waves' of technical

analysis …. A lot of effort has been developed in finance

both by academic and trading institutions and more recently

by physicists (using some of their statistical tools developed

to deal with complex times series) to analyze past data

to get information on the future. The 'Elliott wave' technique

is probably the most famous in this field. We speculate

that the 'Elliott waves', so strongly rooted in the financial

analysts’ folklore, could be a signature of an underlying

critical structure of the stock market."[10]

Paul Tudor

Jones, the billionaire commodity trader, calls Prechter and Frost's

standard text on Elliott "a classic," and one of "the four Bibles

of the business" --

-

- "[McGee

and Edwards'] Technical Analysis of Stock Trends and

The Elliott Wave Theorist both give very specific and

systematic ways to approach developing great reward/risk

ratios for entering into a business contract with the marketplace,

which is what every trade should be if properly and thoughtfully

executed."[11]

Criticism

The premise

that markets unfold in recognizable patterns contradicts the efficient market hypothesis, which

says that prices cannot be predicted from market data such as

moving averages and volume. By this reasoning, if successful market

forecasts were possible, investors would buy (or sell) when the

method predicted a price increase (or decrease), to the point

that prices would rise (or fall) immediately, thus destroying

the profitability and predictive power of the method. In efficient

markets, knowledge of the Elliott wave principle among investors

would lead to the disappearance of the very patterns they tried

to anticipate, rendering the method, and all forms of technical

analysis, useless.

Benoit Mandelbrot

has questioned whether Elliott waves can predict financial markets:

"But Wave

prediction is a very uncertain business. It is an art to which

the subjective judgement of the chartists matters more than

the objective, replicable verdict of the numbers. The record

of this, as of most technical analysis, is at best mixed."[12]

Robert Prechter

had previously said that ideas in an article by Mandelbrot[13]

"originated with Ralph Nelson Elliott, who put them forth more

comprehensively and more accurately with respect to real-world

markets in his 1938 book The Wave Principle."[14]

Critics also

say the wave principle is too vague to be useful, since it cannot

consistently identify when a wave begins or ends, and that Elliott

wave forecasts are prone to subjective revision. Some who advocate

technical analysis of markets have

questioned the value of Elliott wave analysis. Technical analyst

David Aronson wrote:[15]

The Elliott

Wave Principle, as popularly practiced, is not a legitimate

theory, but a story, and a compelling one that is eloquently

told by Robert Prechter. The account is especially persuasive

because EWP has the seemingly remarkable ability to fit any

segment of market history down to its most minute fluctuations.

I contend this is made possible by the method's loosely defined

rules and the ability to postulate a large number of nested

waves of varying magnitude. This gives the Elliott analyst the

same freedom and flexibility that allowed pre-Copernican astronomers

to explain all observed planet movements even though their underlying

theory of an Earth-centered universe was wrong.

Notes

-

R.N. Elliott, R.N. Elliott's Masterworks (New Classics

Library, 1994), 70, 217, 194, 196.

- Poser,

Steven W. (2003). Applying Elliott Wave Theory Profitably,

John Wiley and Sons , pages 2-17.

-

John Casti (31 August 2002). "I know what you'll do next summer".

New Scientist, p. 29.

-

Alex Douglas, "Fibonacci: The man & the markets," Standard

& Poor's Economic Research Paper, February 20, 2001, pp.

8-10. PDF

document here

-

Roy Batchelor and Richard Ramyar, "Magic numbers in the Dow,"

25th International Symposium on Forecasting, 2005, p. 13,

31. PDF document here

-

Robert Prechter (2006), "Elliott Waves, Fibonacci, and Statistics,"

p. 2. PDF

document here

-

Deepak Goel (2006), "Another Look at Fibonacci Statistics."

PDF document

here

-

Robin Wilkin, Riding the Waves: Applying Elliott Wave Theory to the Financial

and Commodity Markets The Alchemist June 2006

- Jordan

Kotick, An Introduction to the Elliott Wave Principle The Alchemist

November 2005

- Sornette,

D., Johansen, A., and Bouchaud, J.P. (1996). "Stock market

crashes, precursors and replicas." Journal de Physique I France

6, No.1, pp. 167–175.

- Mark

B. Fisher, The Logical Trader, p. x (forward)

-

Mandelbrot, Benoit and Richard L. Hudson (2004). The (mis)Behavior

of Markets, New York: Basic Books, p. 245

-

Mandelbrot, Benoit (February 1999). Scientific American,

p. 70.

- Details

here.

-

Aronson, David R. (2006). Evidence-Based Technical Analysis, Hoboken, New Jersey:

John Wiley and Sons, p. 41

References

- Elliott

Wave Principle: Key to Market Behavior by A.J. Frost &

Robert R. Prechter, Jr.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Mastering

Elliott Wave: Presenting the Neely Method: The First Scientific,

Objective Approach to Market Forecasting with Elliott Wave Theory

by Glenn

Neely with Eric Hall. Published by Windsor Books.

- Applying

Elliott Wave Theory Profitably by Steven W. Poser Published

by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

|