A credit

default swap (CDS) is an instrument to transfer the

credit risk of fixed income products . Using technical terms,

it is a bilateral contract under which two counterparties agree

to isolate and separately trade the credit risk of at least

one third-party reference entity. The buyer of a credit swap

receives credit protection. The seller 'guarantees' the credit

worthiness of the product. In more technical language, a protection

buyer pays a periodic fee to a protection seller in exchange

for a contingent payment by the seller upon a credit event (such

as a default or failure to pay) happening in the reference entity.

When a credit event is triggered, the protection seller either

takes delivery of the defaulted bond for the par value (physical

settlement) or pays the protection buyer the difference between

the par value and recovery value of the bond (cash settlement).

Simply, the risk of default is transferred from the holder of

the fixed income security to the seller of the swap. For example,

a mortgage bank, ABC may currently have its credit default swaps

trading at 265 basis points (bp). In other words, it costs 265,000

euros to insure 10 million of its debt per year. A year before,

the same CDS might have been trading at 7 bp, indicating that

markets now view ABC as facing a greater risk of default on

its mortgage obligations.

Credit default

swaps resemble an insurance policy, as they can be used by debt

owners to hedge, or insure against credit events such as a default

on a debt obligation. However, because there is no requirement

to actually hold any asset or suffer a loss, credit default

swaps can also be used to speculate on changes in credit spread.

Credit default

swaps are the most widely traded credit

derivative product[1].

The typical term of a credit default swap contract is five years,

although being an over-the-counter derivative, credit default swaps of

almost any maturity can be traded.

History

In 1995,

J.P. Morgan's Blythe Masters (a 26-year old Cambridge University

graduate hired by the bank), developed the first Credit Default

Swaps and Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDO). On April 2nd,

2007, Masters (who by then was the head of J.P. Morgan's Global

Credit Derivatives group), helped introduce CreditWatchTM

to help evaluate credit swaps among other financial instruments.

By the end

of 2007 there were an estimated USD 45 trillion worth of Credit

Default Swap contracts.[2]

Market

The Bank

for International Settlements reported the notional amount on

outstanding OTC credit default swaps to be $42.6 trillion[[1]]

in June 2007, up from $28.9 trillion in December 2006 ($13.9

trillion in December 2005).

In the US,

the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency reported the notional

amount on outstanding credit derivatives from 882 reporting

banks to be $5.472 trillion at the end of March, 2006.

Structure

and features

Terms

of a typical CDS contract

A CDS contract

is typically documented under a confirmation

referencing the 2003 Credit Derivatives Definitions as published

by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association. The

confirmation typically specifies a reference entity,

a corporation or sovereign which generally, although not always,

has debt outstanding, and a reference obligation, usually

an unsubordinated corporate bond or government bond. The period

over which default protection extends is defined by the contract

effective date and scheduled termination date.

The confirmation

also specifies a calculation agent who is responsible

for making determinations as to successors and substitute

reference obligations, and for performing various calculation

and administrative functions in connection with the transaction.

By market convention, in contracts between CDS dealers and end-users,

the dealer is generally the calculation agent, and in contracts

between CDS dealers, the protection seller is generally the

calculation agent. It is not the responsibility of the calculation

agent to determine whether or not a credit event has occurred

but rather a matter of fact that, pursuant to the terms of typical

contracts, must be supported by publicly available information

delivered along with a credit event notice. Typical CDS

contracts do not provide an internal mechanism for challenging

the occurrence or non-occurrence of a credit event and rather

leave the matter to the courts if necessary, though actual instances

of specific events being disputed are relatively rare.

CDS confirmations

also specify the credit events that will trigger a credit

event and give rise to payment obligations by the protection

seller and delivery obligations by the protection buyer. Typical

credit events include bankruptcy with respect to the

reference entity and failure to pay with respect to its

direct or guaranteed bond or loan debt. CDS written on North

American investment grade corporate reference entities, European

corporate reference entities and sovereigns generally also include

'restructuring' as a credit event, whereas trades referencing

North American high yield corporate reference entities typically

do not. The definition of restructuring is quite technical but

is essentially intended to pick up circumstances where a reference

entity, as a result of the deterioration of its credit, negotiates

changes in the terms in its debt with its creditors as an alternative

to formal insolvency proceedings. This practice is far more

typical in jurisdictions that do not provide protective status

to insolvent debtors similar to that provided by Chapter 11

of the United States Bankruptcy Code. In particular, concerns

arising out of Conseco's restructuring in 2000 led to the credit

event's removal from North American high yield trades.[2]

Finally,

standard CDS contracts specify deliverable obligation characteristics

that limit the range of obligations that a protection buyer

may deliver upon a credit event. Trading conventions for deliverable

obligation characteristics vary for different markets and CDS

contract types. Typical limitations include that deliverable

debt be a bond or loan, that it have a maximum maturity of 30

years, that it not be subordinated, that it not be subject to

transfer restrictions (other than Rule 144A), that it be of

a standard currency and that it not be subject to some contingency

before becoming due.

Quotes

of a CDS contract

Sellers

of CDS contracts will give a par quote (see par value)

for a given reference entity, seniority, maturity and restructuring

e.g. a seller of CDS contracts may quote the premium on a 5

year CDS contract on Ford Motor Company senior debt with modified

restructuring as 100 basis points. The par premium is calculated

so that the contract has zero present value on the effective

date. This is because the expected value of protection payments

is exactly equal and opposite to the expected value of the fee

payments. The most important factor affecting the cost of protection

provided by a CDS is the credit quality (often proxied by the

credit rating) of the reference obligation. Lower credit ratings

imply a greater risk that the reference entity will default

on its payments and therefore the cost of protection will be

higher.

The swap

adjusted spread of a CDS should trade closely with that of the

underlying cash bond issued by the reference entity. Misalignments

in spreads may occur due to technical minutiae such as specific

settlement differences, shortages in a particular underlying

instrument, and the existence of buyers constrained from buying

exotic derivatives. The difference between CDS spreads and Z-spreads

or asset swap spreads is called the basis.

Pricing

and valuation

There are

two competing theories usually advanced for the pricing of credit

default swaps. The first, which for convenience we will refer

to as the 'probability model', takes the present value of a

series of cashflows weighted by their probability of non-default.

This method suggests that credit default swaps should trade

at a considerably lower spread than corporate bonds.

The second

model, proposed by Darrell Duffie, but also by Hull and White,

uses a no-arbitrage approach.

Under the

probability model, a credit default swap is priced using a model

that takes four inputs: the issue premium, the recovery rate,

the credit curve for the reference entity and the LIBOR curve.

If default events never occurred the price of a CDS would simply

be the sum of the discounted premium payments. So CDS pricing

models have to take into account the possibility of a default

occurring some time between the effective date and maturity

date of the CDS contract. For the purpose of explanation we

can imagine the case of a one year CDS with effective date t0

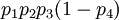

with four quarterly premium payments occurring at times t1, t2, t3, and t4. If the nominal for the CDS is N and the issue premium is c then the size of the quarterly premium payments

is Nc / 4. If we assume for

simplicity that defaults can only occur on one of the payment

dates then there are five ways the contract could end:

either it does not have any default at all, so the four premium

payments are made and the contract survives until the maturity

date, or a default occurs on the first, second, third

or fourth payment date. To price the CDS we now need to

assign probabilities to the five possible outcomes, then

calculate the present value of the payoff for each outcome.

The present value of the CDS is then simply the present value

of the five payoffs multiplied by their probability of occurring.

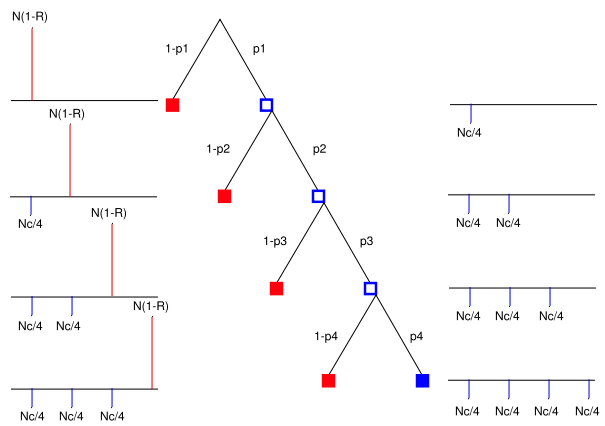

This is

illustrated in the following tree diagram where at each payment

date either the contract has a default event, in which case

it ends with a payment of N(1 ŌłÆ

R) shown in red, where R is the recovery rate, or it survives without a default

being triggered, in which case a premium payment of Nc / 4 is made, shown in blue. At either side of the

diagram are the cashflows up to that point in time with premium

payments in blue and default payments in red. If the contract

is terminated the square is shown with solid shading.

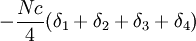

The probability

of surviving over the interval ti ŌłÆ 1 to ti without a default payment is

pi and the

probability of a default being triggered is 1

ŌłÆ pi. The calculation of present

value, given discount factors of 1

to ┤4 is then

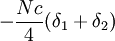

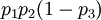

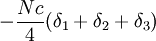

| Description |

Premium Payment PV |

Default Payment PV |

Probability |

| Default at time t1 |

|

|

|

| Default at time t2 |

|

|

|

| Default at time t3 |

|

|

|

| Default at time t4 |

|

|

|

| No defaults |

|

|

|

The probabilities

p1, p2, p3, p4 can be calculated using

the credit spread curve. The probability of no default

occurring over a time period from t to t + Δt

decays exponentially with a time-constant determined by the

credit spread, or mathematically p = exp( ŌłÆ s(t)╬öt)

where s(t) is the credit spread zero curve at time

t. The riskier the reference

entity the greater the spread and the more rapidly the survival

probability decays with time.

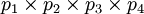

To get the

total present value of the credit default swap we multiply the

probability of each outcome by its present value to give

In the 'no-arbitrage'

model proposed by both Duffie, and Hull and White, it is assumed

that there is no risk free arbitrage. Duffie uses the LIBOR

as the risk free rate, whereas Hull and White use US Treasuries

as the risk free rate. Both analyses make simplifying assumptions

(such as the assumption that there is zero cost of unwinding

the fixed leg of the swap on default) which may invalidate the

no-arbitrage assumption. However the Duffie approach is frequently

used by the market to determine theoretical prices. Under

the Duffie construct, the price of a credit default swap can

also be derived by calculating the asset swap spread of a bond.

If a bond has a spread of 100, and the swap spread is 70 basis

points, then a CDS contract should trade at 30. However owing

to inefficiencies in markets, this is not always the case.

The difference between the theoretical model and the actual

price of a credit default swap is known as the basis. There

is very little academic research which identifies the factors

that cause the basis to expand and contract

Uses

Like most

financial derivatives, credit default swaps can be used to hedge existing exposures to credit risk, or to speculate

on changes in credit spreads.

Hedging

Credit default

swaps can be used to manage credit risk without necessitating

the sale of the underlying cash bond. Owners of a corporate

bond can protect themselves from default risk by purchasing

a credit default swap on that reference entity.

For example,

a pension fund owns $10 million worth of a five-year bond issued by Risky Corporation. In order to manage their

risk of losing money if Risky Corporation defaults on its debt,

the pension fund buys a CDS from Derivative Bank in a notional

amount of $10 million which trades at 200 basis points. In return

for this credit protection, the pension fund pays 2% of 10 million

($200,000) in quarterly installments of $50,000 to Derivative

Bank. If Risky Corporation does not default on its bond payments,

the pension fund makes quarterly payments to Derivative Bank

for 5 years and receives its $10 million loan back after 5 years

from the Risky Corporation. Though the protection payments reduce

investment returns for the pension fund, its risk of loss in

a default scenario is eliminated. If Risky Corporation defaults

on its debt 3 years into the CDS contract, the pension fund

would stop paying the quarterly premium, and Derivative Bank

would ensure that the pension fund is refunded for its loss

of $10 million (either by taking physical delivery of the defaulted

bond for $10 million or by cash settling the difference between

par and recovery value of the bond). Another scenario would

be if Risky Corporation's credit profile improved dramatically

or it is acquired by a stronger company after 3 years, the pension

fund could effectively cancel or reduce its original CDS position

by selling the remaining two years of credit protection in the

market.

Speculation

Credit default

swaps give a speculator a way to make a large profit from changes

in a company's credit quality. A protection seller in a credit

default swap effectively has an unfunded exposure to the underlying

cash bond or reference entity, with a value equal to the notional

amount of the CDS contract.

For example,

if a company has been having problems, it may be possible to

buy the company's outstanding debt (usually bonds) at a discounted

price. If the company has $1 million worth of bonds outstanding,

it might be possible to buy the debt for $900,000 from another

party if that party is concerned that the company will not repay

its debt. If the company does in fact repay the debt, you would

receive the entire $1 million and make a profit of $100,000.

Alternatively, one could enter into a credit default swap with

the other investor, by selling credit protection and receiving

a premium of $100,000. If the company does not default, one

would make a profit of $100,000 without having invested anything.

It is also

possible to buy and sell credit default swaps that are outstanding.

Like the bonds themselves, the cost to purchase the swap from

another party may fluctuate as the perceived credit quality

of the underlying company changes. Swap prices typically decline

when creditworthiness improves, and rise when it worsens. But

these pricing differences are amplified compared to bonds. Therefore

someone who believes that a company's credit quality would change

could potentially profit much more from investing in swaps than

in the underlying bonds (although encountering a greater loss

potential).

Criticisms

Warren Buffett

famously described derivatives bought speculatively as "financial

weapons of mass destruction." In Berkshire Hathaway's annual

report to shareholders in 2002, he said "Unless derivatives

contracts are collateralized or guaranteed, their ultimate value

also depends on the creditworthiness of the counterparties to

them. In the meantime, though, before a contract is settled,

the counterparties record profits and losses -often huge in

amount- in their current earnings statements without so much

as a penny changing hands. The range of derivatives contracts

is limited only by the imagination of man (or sometimes, so

it seems, madmen)." The same report, however, also states

that he uses derivatives to hedge, and that some of Berkshire

Hathaway's subsidiaries have sold and currently sell derivatives

with notional amounts in the tens of billions of dollars.

The market

for credit derivatives is now so large, in many instances the

amount of credit derivatives outstanding for an individual name

are vastly greater than the bonds outstanding. For instance,

company X may have $1 billion of outstanding debt and $10 billion

of CDS contracts outstanding. If such a company were to default,

and recovery is 40 cents on the dollar, then the loss to investors

holding the bonds would be $600 million. However the loss to

credit default swap sellers would be $6 billion. In addition

to spreading risk, credit derivatives, in this case, also amplify

it considerably.

Another

major issue is the vast difference in knowledge concerning the

creditworthiness of the underlying borrower. Major banks and

investment banks, like JP Morgan Chase, Citigroup, Bank of America,

Merrill Lynch, Goldman Sachs, Lehman Brothers, etc., are usually

the originators of syndicated loans or the underwriters of stock

and bonds of the companies in question. Credit swaps are issued,

by these same banks, against the credit of those companies.

JP Morgan and its cousins have a much better idea whether or

not particular borrowers are really at risk of default, because

of their relationships with those borrowers. This can be deemed

"inside" information, which would be illegal to possess while

actively trading in a particular market, in almost any other

field of market activity. Yet, within the credit default swap

trading community, insider trading is not only a given, but

is the fundamental basis upon which the entire structure depends.

Indeed, these same major banking institutions also dominate

the market for issuance of derivatives, generally.

Derivatives

such as credit default swaps also create major distortions in

the traditional indicators of value of stock and bond markets.

Many people wonder why indices like the Dow Jones Industrial

Average and S&P 500 seem to go up endlessly. Part of the

reason is that big institutional investors no longer sell companies

they feel are about to fail, no matter how obvious that impending

failure may be. The securities issued by such companies may

retain significant paper value up until almost the very end.

Instead of selling, investors can buy "insurance" in the form

of derivatives and keep holding their investments. This distorts

the value of traditional market indices because the decision

to remove a failing company from the index can be made well

before the paper value drops to zero. This saves the value of

the index. It creates the false impression that the index always

rises. The underlying markets, for which the index was developed

to reflect value, may be far more unstable than appearances

indicate. False appearances of stability allow securities markets

to appear far less risky than they really are, encourage less

knowledgeable players to speculate on derivatives, and allow

broker/dealers, financial journalists and some academics to

claim that markets are far better investments for the retail

investor than they really are. The overall effect is to reduce

the perception of risk even though the risk still exists. The

reduced perception, however, reduces risk premiums and encourages

shoddy loan practices, and may be the cause of runaway financial

bubbles, when irrational exuberance gains traction on the basis

of inaccurate information.

However,

for informed investors, CDS premiums can act as a good barometer

of company's health. If investors are not sure about a firm's

credit quality they will demand protection thus pushing up CDS

spreads on that name in the market. Equity markets will then

draw a cue from the credit markets and push down the stock price

based on fear of corporate default.

Operational

issues in settlement

In the US,

the settlement and processing of a CDS contract is currently

the subject of concern by the US Federal Reserve. In 2005, the

Federal Reserve obtained a commitment by 14 major dealers to

upgrade their systems and reduce the backlog of "unprocessed"

CDS contracts. As of January 31, 2006, the dealers had met their

commitment and achieved a 54% reduction.[3]

In addition,

growing concern over the sheer volume of CDS contracts potentially

requiring physical settlement after credit events for names

actively traded in the single-name and index-trade market where

the notional value of CDS contracts dramatically exceeds the

notional value of deliverable bonds has led to the increasing

application of cash settlement auction protocols coordinated

by ISDA. Successful auction protocols have been applied following

credit events in respect of Collins & Aikman Products Co.,

Delphi Corporation , Delta Air Lines and Northwest Airlines,

Calpine Corporation, Dana Corporation and Dura Operating Corp..

LCDS

A new type

of default swap is the "loan only" credit default swap (LCDS).

This is conceptually very similar to a standard CDS, but unlike

"vanilla" CDS, the underlying protection is sold on syndicated

secured loans of the Reference Entity rather than the broader

category of "Bond or Loan". Also, as of May 22, 2007, for the

most widely traded LCDS form which governs North American single

name and index trades, the default settlement method for LCDS

shifted to auction settlement rather than physical settlement.

The auction method is essentially the same as that which has

been used in the various ISDA cash settlement auction protocols

but does not require parties to take any additional steps following

a credit event (i.e., adherence to a protocol) to elect cash

settlement. On October 23, 2007, the first ever LCDS auction

was held for Movie Gallery.[4]

Because

LCDS trades are linked to secured obligations with much higher

recovery values than the unsecured bond obligations that are

typically assumed to be cheapest to deliver in respect of vanilla

CDS, LCDS spreads are generally much tighter than CDS trades

on the same name.

External

links

- Explanatory Diagram from the New York Times

- 2003 ISDA Credit Derivatives Template

- BIS - Regular Publications

- OCC - Quarterly

Derivatives Fact Sheet

- A Beginner's Guide

to Credit Derivatives - Noel Vaillant, Nomura International

- Documenting credit default swaps on asset backed securities, Edmund

Parker and Jamila Piracci, Mayer, Brown, Rowe & Maw, Euromoney

Handbooks.

- A billion-dollar game for bond managers

- Hull, J. C. and A. White, Valuing Credit Default Swaps I: No Counterparty

Default Risk

- Hull,

J. C. and A. White, Valuing Credit Default Swaps II: Modeling

Default Correlations

- Elton et al, Explaining the rate spread on corporate bonds

In

the News

References

- British Banker Association Credit Derivatives Report.

-

Morgensen, Gretchen. "Arcane Market Is Next to Face Big Credit Test", The New York

Times, 2008-02-17. Retrieved on 2008-02-17.